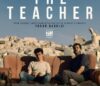

‘The pigeons make me feel free’: An old pastime thrives in a Palestinian refugee camp

To entice others back to the coop, Qum holds up a female pigeon. “The pigeons make me feel free,” he says. (Linda Davidson/The Washington Post)

Photos By: Linda Davidson. Writer: William Booth

Source: The Washington Post

JERUSALEM — As the afternoon heat retreats and the light becomes a little rosy in the Palestinian towns across the West Bank and Gaza, you can hear something curious above your head if you listen closely.

Up on the roofs of the cement-block buildings of the Shuafat refugee camp in East Jerusalem, there’s the sound of fast clapping. Bap, bap, bap! Down the warren of streets, high above, sharp whistles. Above the bakery, someone is slapping a metal bar. Above the carwash, an unseen hand cracks a horsewhip.

These are the Palestinian pigeon fanciers — and they are flying their flocks. The sounds the men are making — individual, unique whistles and snaps — urge their birds to fly further and higher, or to come home.

Breeding, showing, trading, selling, flying and racing pigeons is an old pastime in the Middle East, pursued by Arabs and Jews alike.

Ten years ago, a construction contractor named Mohammed Qinabi brought a flock to his rooftop in Shuafat. He had learned the art in neighboring Jordan, where he lived for a time and where keeping pigeons is almost a national sport.

His neighbors liked what they saw, how Qinabi could command a flock of 30 or 40 birds to wheel and dive over his head — and then come back to his handmade cages and coops when he called them.

“Now, many have become addicted,” Qinabi said.

He was only half-kidding. “Once you start with the pigeons,” he said, “it’s hard for some to stop.”

These days, more than two dozen men fly pigeons in the camp, he said. Feed is cheap. Cages and coops are just a bit of castoff wood and wire. But a healthy athletic male, with beautiful plumage? A leader? Those can easily cost a few hundred dollars. A pair of fancy show birds can go for several thousand dollars.

The 40-year-old laborer stood on his roof, watching a mob of birds circle above. “A bird in the sky is not your bird,” he said. “It’s only yours when it lands.”

Qinabi has 82 birds. When a neighbor asks how many children he has, he jokingly responds, “Eighty-two.” He knows each one by sight. His birds wear colored bands on their feet, and some have little bells.

Shuafat is a tough neighborhood of narrow streets and chaotic building. It is notorious for drug sales, criminal clans, blood feuds. Officially part of the Jerusalem municipality, the camp is today a city of 24,000, though nobody knows its true size. It lies on the other side of the checkpoint through Israel’s separation barrier, here an ugly cement wall. Israel doesn’t really provide much in the way of services — the garbage often piles up, until someone burns it.

“We’re a kind of no man’s land,” Qinabi said.

He said that pigeon fanciers traditionally had a rough reputation, that it was a sport for outlaws. “But here,” he said, “all the fanciers are nice guys.”

He explained that part of the allure of flying pigeons is the mastery over the birds — the fancier raises them, feeds them, trains them. And the birds develop a powerful attachment to home and owner.

“You have to be a master to control a bird in the sky,” Qinabi said.

Like flying a kite? He shook his head. No, nothing like flying a kite. “A kite has a string,” he said. “The master of the game is the one who brings all his birds back. Each one is very valuable to me. If I lose one pigeon, I cannot sleep.”

Yazen al-Qum, 20, runs a car-washing business across the street. Qinabi introduced him to “this obsession” two years ago, he said.

He said he spends all his free time caring for his birds, flying them or thinking about them.

“Flying pigeons is a state of mind. I am up on my roof. I am high. I feel like a king of my world,” Qum said. He let out a high-pitched whistle, his personal call.

He watched as his flock circled Shuafat, crossed the dry valley below, flew above the separation barrier, and soared over Pisgat Zeev, a neighboring Jewish settlement.

“The pigeons make me feel free,” he said. “Through their eyes I go everywhere, I see everything. You know the walls, the places I cannot go? There’s no wall for the birds. They’re above all this.”

Sufian Taha contributed to this report.

Yazen al-Qum’s pigeons. He runs a car-washing business across the street and says he was introduced to “this obsession” two years ago.

Qum holds his lead male pigeon with a bell and bands. The bell makes it easier to locate a bird in flight, and the green and red bands identify it as his.

“Flying pigeons is a state of mind,” Qum says. “I am up on my roof. I am high. I feel like a king of my world” in the refugee camp.

“Through their eyes I go everywhere, I see everything. You know the walls, the places I cannot go? There’s no wall for the birds. They’re above all this.”