Cross-cultural Craft: An Intersection Between Arabic Calligraphy And Western Art

By: Laila Mamdouh / Arab America Contributing Writer

What if words could move? What if letters could gallop like horses, glow like candles, or rise like domes against the sky? In Arabic calligraphy, this is not just imagination, it is tradition. For centuries, Muslim artists have transformed sacred text into flowing visual patterns that are as expressive as they are legible. However, a new current of creativity has brought Arabic calligraphy into dialogue with Western painting, where brushstrokes, shadows, and abstract forms expand the script into new aesthetic dimensions.

The result is a meeting of worlds: works that remain deeply rooted in Arabic heritage yet speak fluently in the global language of modern art. To see this dialogue unfold, let’s journey through five works where Arabic letters are not merely written but lived.

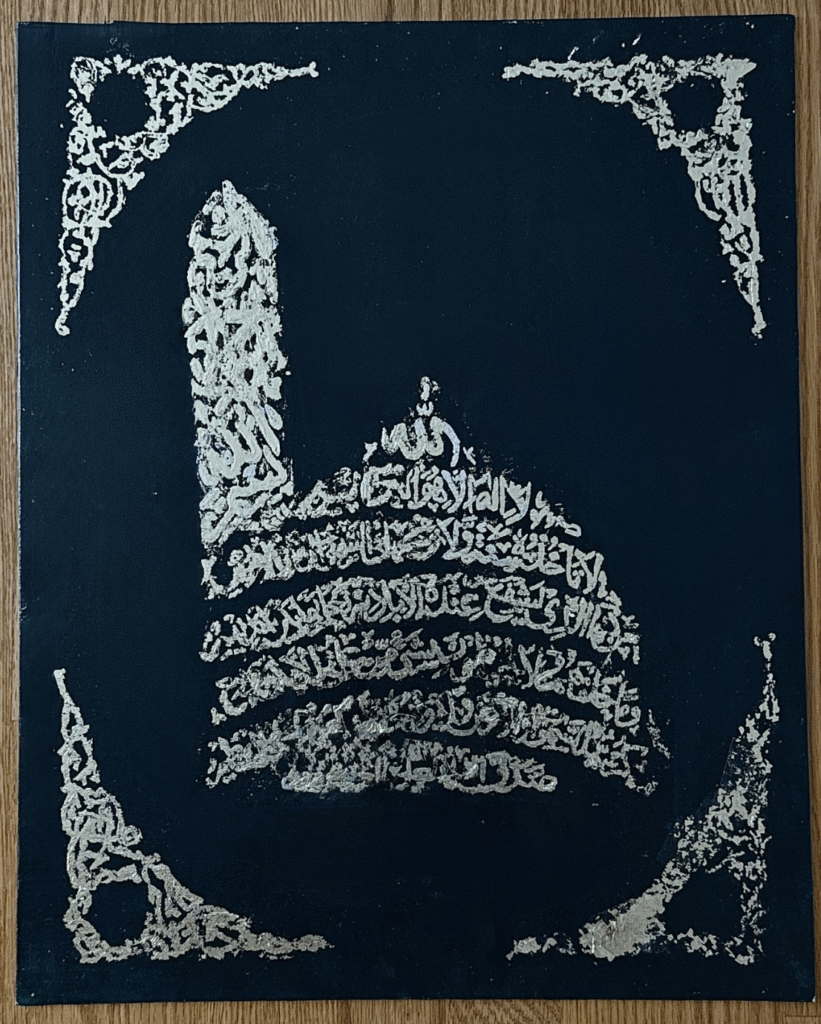

The Dome of Faith

The first piece rises like a mosque built on canvas. A dome and minaret, glowing in gold against a black background, are constructed not from stone but from Quranic verses layered arch by arch. Architecture here becomes script: a building erected out of language itself.

This image carries echoes of Islamic art, where Quranic inscriptions crown domes, arches, and mihrabs, ensuring that worshipers are literally enveloped by divine words. Yet it also resonates with Western abstraction. Modern painters such as Antoni Tàpies or Mark Rothko used flat surfaces and luminous contrasts to evoke transcendence beyond the material. Here, too, spirituality is suggested not by depiction but by texture, rhythm, and radiance. The dome is no longer just an architectural form; it becomes a metaphor for faith itself, rising from the immaterial body of text.

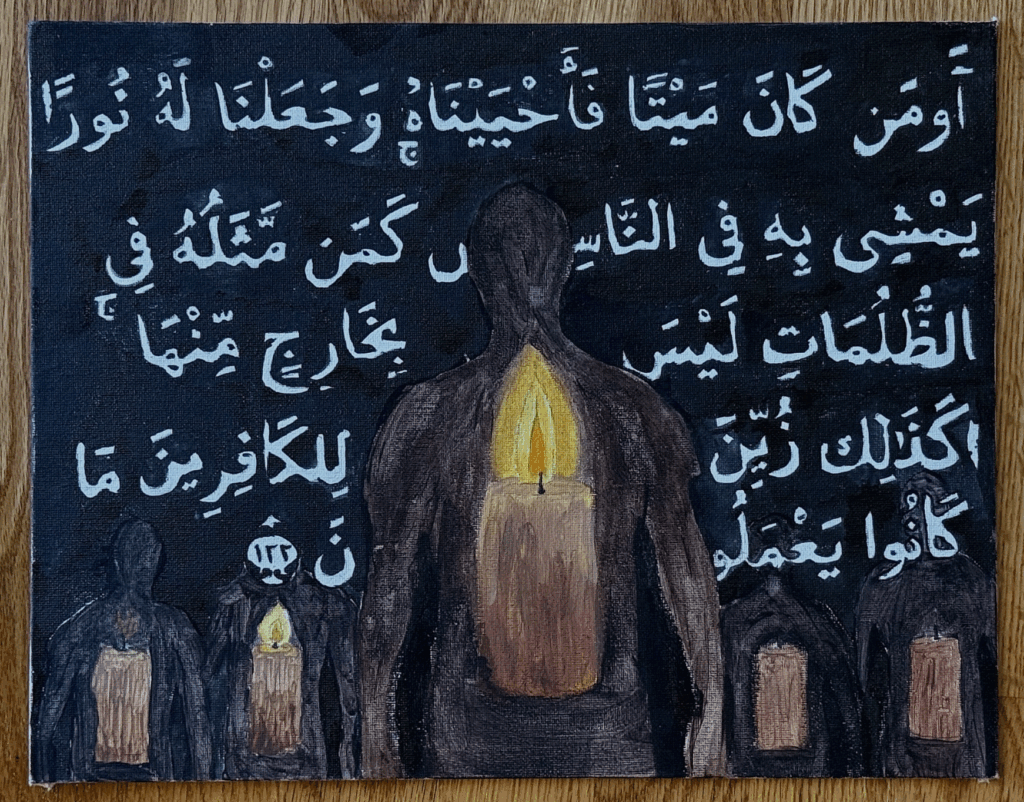

From structures to souls, the second piece shifts toward the human figure. Silhouettes of bodies glow from within, each chest illuminated by a small candle. Quranic verses flow in white script across the surrounding blackness, as though the words themselves fuel the inner flame.

Light in the Darkness

The symbolism is striking. Faith is not external; it is a light carried within, a fire sparked by divine speech. This recalls Western traditions where light functions as a metaphor for truth, the dramatic bursts of light in Caravaggio’s paintings or the glowing splendor of Baroque altarpieces.

Yet Arabic calligraphy introduces a linguistic dimension: the glow comes from words, not from paint alone. Light here is not an abstract idea but a literal verse embodied in human form, binding Islamic spirituality to Western visual strategies of Chiaroscuro.

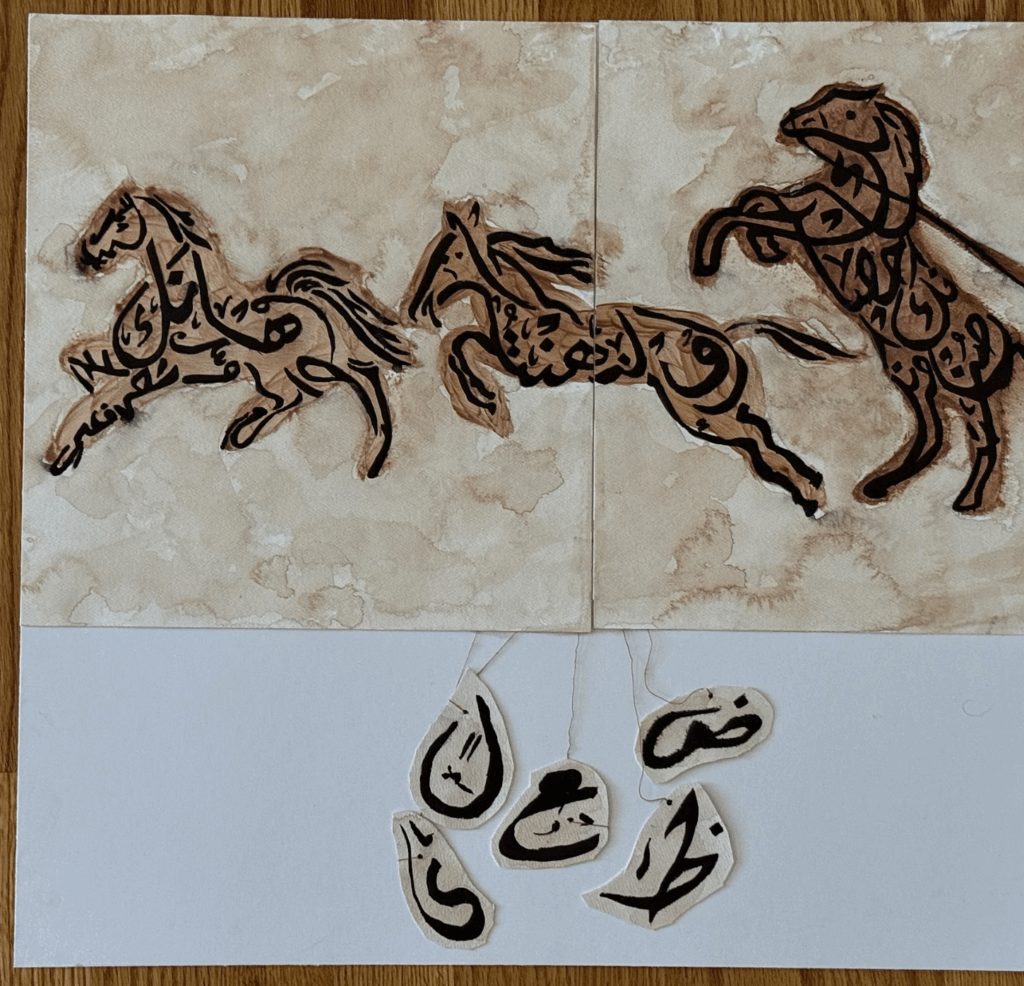

Galloping Verses

The third canvas unleashes pure motion. Horses charge forward, but their bodies are woven entirely out of Arabic letters. Every sinew, every stride, is drawn with script, so that the animals themselves seem to be made of language.

The horse occupies a privileged place in both traditions. In Arab culture, it is a symbol of nobility, beauty, and divine strength, celebrated in poetry and honored in warfare. In Western art, from Leonardo da Vinci’s studies to Romantic equestrian portraits, the horse represents energy, freedom, and power.

Yet this work pushes further: here, It is not pigment or anatomy that animates the scene but language itself. The script surges forward; the letters stride like living bodies. The momentum evokes the dynamism of Futurism, that Western celebration of velocity and motion, yet here the engine is not steel or machine but text—words themselves transformed into pure movement. In doing so, it transforms language into pure kinetic force.

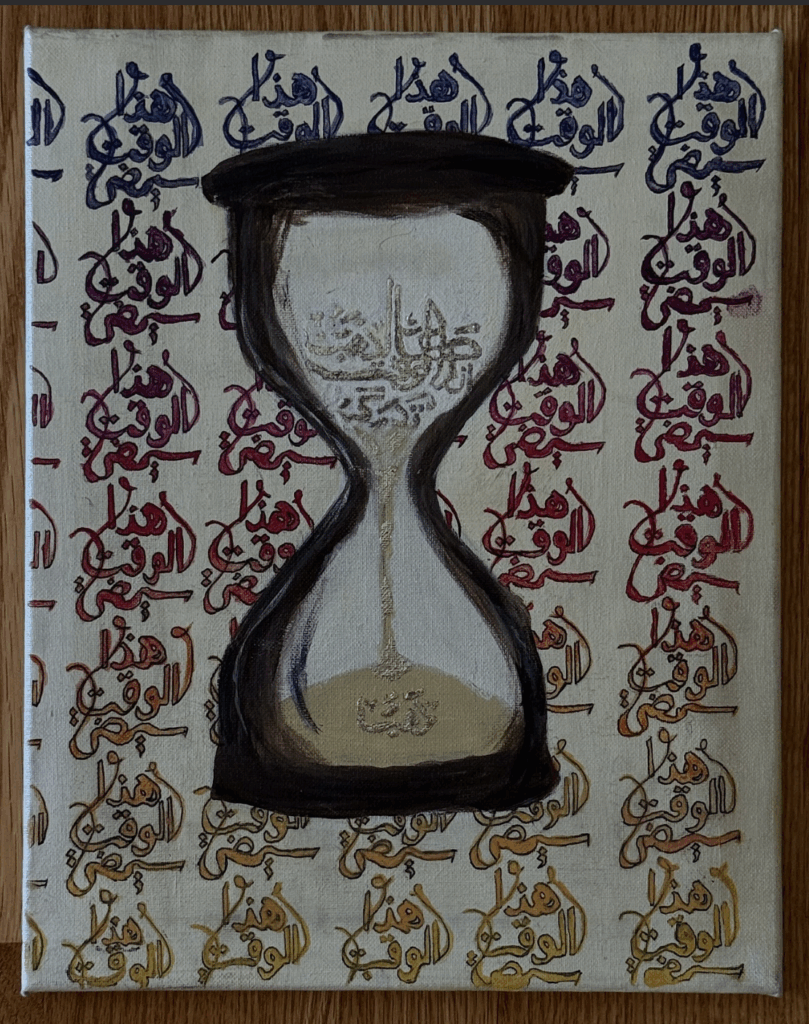

The Hourglass of Script

If the horses embody movement, the fourth piece contemplates time. At its center stands an hourglass, a quintessential Western emblem of mortality. But instead of sand, it contains cascading Arabic letters, pouring downward and collecting at the base.

This substitution reframes a familiar symbol. In European Vanitas paintings, the hourglass warned of life’s transience, its grains measuring out inevitable decay. Here, however, what passes through time is not matter but meaning. Words, not dust, fill the vessel, suggesting that what endures is not flesh but the truths inscribed in language.

The colors reinforce the cycle: calligraphy shifts from cool blues and purples at the top through fiery reds to luminous gold below, tracing the arc of day, life. The fusion is structural as well as symbolic: the Western motif of the hourglass becomes animated by Arabic script, transforming a meditation on death into one on destiny, continuity, and the persistence of words.

Time as a Sword

The final piece grounds this reflection in the tangible. A clock of pale wood, sharp in its minimalist design, would fit neatly into the tradition of modern Western functionalism, clean, ordered, rational. Yet across its face, slicing diagonally through its center, runs a bold line of Arabic calligraphy: the proverb, “Time is like a sword: if you do not cut it, it cuts you.”

The phrase redefines the object. No longer a neutral instrument of measurement, the clock becomes a stage where language carves meaning into each passing second. The proverb resonates with Western traditions in which timepieces appear as reminders of mortality, yet it diverges by making the text integral to the design itself.

Unlike Western Vanitas paintings, where clocks and inscriptions were placed side by side, here the boundaries dissolve: the script and mechanism fuse. The calligraphy does not decorate the clock; it becomes the clock’s essence, its very heartbeat.

This synthesis recalls the ideals of the Arts and Crafts and Bauhaus movements, where utility and beauty were merged. Yet the Arabic script adds a metaphysical charge, time is not only kept but narrated, given depth and urgency through words.

When Words Become Worlds

Together, these five works reveal a profound truth: Arabic calligraphy is not static ink on paper but a living, breathing medium. It can rise into domes, shine through bodies, gallop as horses, flow through hourglasses, or slice through clocks. Each piece demonstrates that words do not merely say something; they become something.

Placed alongside Western traditions, from Renaissance light to Futurist motion, from Vanitas symbols to Bauhaus minimalism, these works are not imitations or hybrids but conversations. They show that art, whether Eastern or Western, ultimately seeks the same goal: to give form to the unseen, to render visible the forces that shape human experience.

In the meeting of Arabic calligraphy and Western painting, words transcend their linguistic boundaries. They move, they breathe, they endure. They become worlds. Alive. Luminous. And endlessly in motion.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!