Ishtar Review: The Film That Was Destined to Fail

By: María Teresa Fidalgo-Azize/ Arab American Contributing Writer.

The movie is a long dry slog. It’s not funny. It’s not smart, it’s interesting only in the way a traffic accident is interesting

Robert Ebert

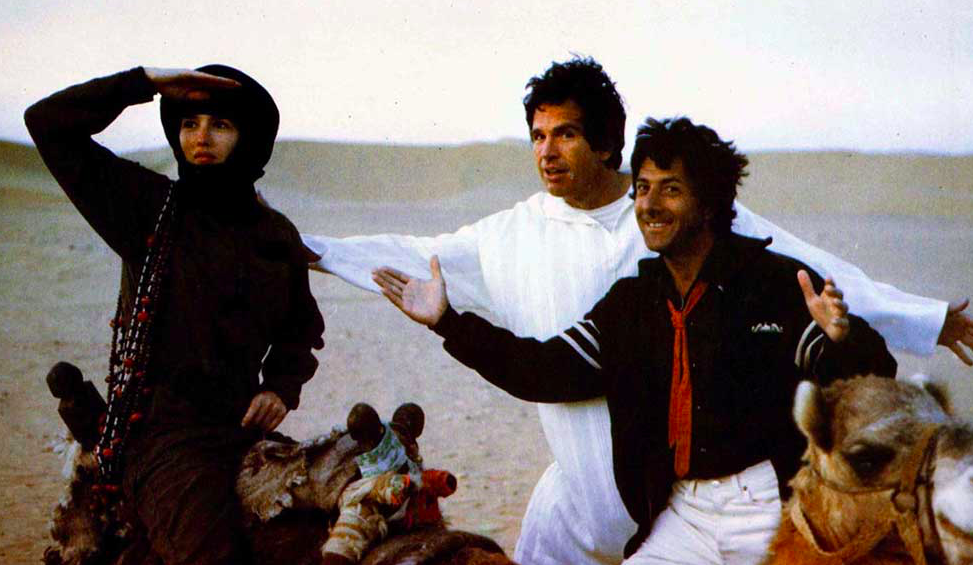

Dustin Huffman and Warren Beatty are two endearing modern daydreaming misfit songwriters. Adulthood coming of age in the “exotic” and Orientalist location of the mythic land of Ishtar. CIA operatives are aiding a despotic wealthy emir, opposing the country’s revolution, which is categorically dismissed as “communist.” An American Jewish man “acts like an Arab” and speaks gibberish to communicate with arms dealers with local tribal Berbers.

This wreckage describes Ishtar[1], the 51-million-dollar production cost of the 1987 film directed by Elaine May. A film that, before its screening, was vandalized with accusations and criticism of being one of the worst films of all time, a notoriety that led to the forty-year absence of the once revered director Elaine May.

More than 30 years after its premiere, recent articles and even a documentary have come to defend Ishtar not as a comedy masterpiece but as a quirky, misunderstood film that speaks lightheartedly with some existentialist humor about friendships and American intervention without ever assuming the position of “serious foreign policy” discourse.

Film Analysis

This is an ancient, devious world, and you come from a young country. Promise me you will keep my secret without trying to understand it.

Shirra Assell

There is an age when the promise of “potential” guarantees nothing. This is where Warren Beatty (Lyle Rogers) and Dustin Hoffman (Chuck Clarke) stand as a 40-something oddball singer/songwriter duo. Their songs titled “That’s Amore” and “Hot Fudge Love” reminisce on a time of childlike innocence; there is barely a scratch of experience to them. Lyle Rogers and Chuck Clarke’s depiction eludes politicization until they are booked as showmen for an act in Morocco.

Despite being rejected and pronounced “unmarketable” for American audiences, the epicenter of global success, Lyle and Chuck venture for success outside their reality: unknowingly, they become part of the great explorers. Arriving in the mythic land of Ishtar, the crossing point into Morocco, Chuck is seduced by the rebel Shirra Assell (Isabelle Adjani), who endeavors to overthrow the emir’s dictatorship, which the CIA backs.

The portrayal of Chuck falling prey to a “damsel in distress” speaks not only of his gullibility when handing his passport to Shirra but also of his acute ignorance of US international politics as an American civilian. Chuck and Lyle arrive in Ishtar embodying the willful ignorance of US citizens regarding their nation’s role as an imperial force, be it in influence or intervention.

The plot develops the storyline of Chuck and Lyle as crucial figures in the future of Ishtar, seduced by Shirra, the rebel, and simultaneously pawns for the CIA in scenes that portray a ludicrous mess. Referencing this section’s introductory quote, there is much of the native landscape that we, as viewers and Chuck and Lyle as Americans, cannot comprehend- we are from a land of inexperience, and there is a destructive mystique to Ishtar.

Film and media scholars would argue about the representation of Ishtar and Morocco as the otherization of the Arab World. They would signal scenes that, by today’s standards, would be subject to cancel culture. For instance, when Chuck “acts as an Arab,” a group of men named Mohammed tries to swindle Lyle. Yet this absolute judgment dismisses how Elaine May’s direction laughs at this comedy of errors by accentuating Americans’ foreignness and hypocrisy regarding another country’s customs and internal affairs.

Conclusion

Ishtar is no philosophical meditation on American policy or a masterclass on the comedy genre. However, despite what it lacks, its villainization as one of the worst films ever is unwarranted. Elaine May’s fallout from Hollywood’s grace indicates how the film’s criticism grew beyond the image shown in Ishtar to signal the elaborate cost management of its production. Amidst today’s polarizing zeitgeist, I suggest rewatching the film without the expectation of either pointing out something “problematic” or expecting an academic-approved tale of American foreign policy. Sometimes, one has to unplug and risk laughing regardless of its fleetingness.

Sources:

Brody, Richard. “Elaine May Talks about ‘Ishtar.’” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 1 Apr. 2016, www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/elaine-may-talks-about-ishtar.

Ebert, Roger. “Ishtar Review”. Roger Ebert.com, May 15, 1987. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ishtar-1987

May, Elaine, director. Ishtar. Columbia Pictures, 1987.

Mitchell, John and Jonathan Crombie, directors. Waiting for Ishtar. Vimeo, 14 Dec. 2017, https://vimeo.com/247355864.

Morris, Brogran. “Hear Me Out: Why Ishtar Isn’t a Bad Movie.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 June 2021, www.theguardian.com/film/2021/jun/07/ishtar-warren-beatty-dustin-hoffman-film-elaine-may.

Reid, Joe. “‘Ishtar’ at 30 and the Legacy of the Giant Hollywood Flop.” Decider, Decider, 15 May 2017, www.decider.com/2017/05/15/ishtar-30th-anniversary/.

[1] In Mesopotamia, Ishtar, also known as Inanna, was the goddess of love, sex, and war.

Check out Arab America’s blog here!