Pathbreakers of Arab America: Edward Said

By: John Mason / Arab America Contributing Writer

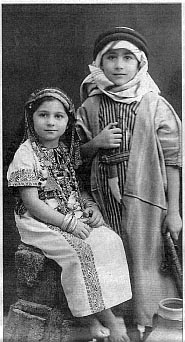

This is the nineteenth in Arab America’s series on American pathbreakers of Arab descent. The series includes personalities from entertainment, business, sports, science, academia, journalism, and politics, among other areas. Our nineteenth pathbreaker is Edward Wadie Said. A Palestinian American, he was born in Jerusalem during the British Mandate period in 1935 to parents Wadie and Hilda Said, a business family. Said is a renowned scholar, literary critic, political activist, and musician. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he is known as one of the founders of postcolonial studies, a school of thought which is highly critical of the ill effects of Western colonialism.

Palestinian, Arab, American identities, Arabic, English, French languages, cross-cultural currents shaping a young, alienated Said

Said, whose parents were Christian, spent his formative years in the Arab Middle East, including early schooling in Cairo at the Egyptian branch of Victoria College. According to Wikipedia’s bio on Said, his classmates at Victoria “included Hussein of Jordan and the Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, and Saudi Arabian boys whose academic careers would progress to their becoming ministers, prime ministers, and leading businessmen in their respective countries.”

By virtue of his father’s voluntary service to the U.S. Army during World War I, Said had American citizenship. That, along with his English first name, Palestinian background, and a mix of Arabic and English languages, stood out among his Arab classmates. Again, according to Wikipedia, Said complained, “To make matters worse, Arabic, my native language, and English, my school language, were inextricably mixed: I have never known which was my first language, and have felt fully at home in neither, although I dream in both. Every time I speak an English sentence, I find myself echoing it in Arabic, and vice versa.” Such cross-cultural anomalies later comprised Said’s 2002 essay, ”Between Worlds, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays.”

Expelled from Victoria College for being a “troublesome boy,” Said attended Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts, “a socially élite, college-prep boarding school where he lived a difficult year of social alienation.” Regardless of his not always fitting well as an adolescent into elite schools, he always excelled academically. Said attributes his alienation to his parents’ decision to send him “as far away as possible.” Nonetheless, he excelled academically and achieved the highest school rankings. Said prided himself on his academic achievements, and subsequently went on to graduate from Princeton in 1957 with a B.A. an M.A., and Ph.D. from Harvard. Said was also an accomplished concert pianist.

Said’s professional academic career was nothing less than stellar, starting in 1963 as a member of the English and Comparative Literature faculties at Columbia; he had visiting professorships at Harvard, Stanford, Johns Hopkins, and Yale, among several others. He served as editor of the Arab Studies Quarterly and held memberships in numerous academic councils; Said authored numerous books, including “Culture and Imperialism” (1993) and “Orientalism” (1978). The latter concerns how the Western world perceives the Orient and it introduced an entirely new, controversial way of how to analyze texts or narratives.

According to Wikipedia, Orientalism is defined in Said’s book by the same title as: “a critical concept to describe the West’s commonly contemptuous depiction and portrayal of The East, i.e. the Orient. Societies and peoples of the Orient are those who inhabit the places of Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East. Said argues that Orientalism, in the sense of the Western scholarship about the Eastern World, is inextricably tied to the imperialist societies who produced it, which makes much Orientalist work inherently political and servile to power.”

However, Said’s Orientalism was more than just an academic concept for him—it was part and parcel of his own sense of alienation that had shaped him as a child and continued into his adult life. It resulted in his own agenda for political action, much of it directed to his passion for the defense of a state of their own for Palestinians. How relevant is that for these days when many Palestinians seem to be just on the edge of survival, much less the remote possibility of independence?

A champion of Palestine and Palestinians everywhere, Edward Said translated his literary ideas into political action

As a well-known public and intellectual figure, Said criticized Israel and Arab countries, especially “the political and cultural policies of Islamic régimes who acted against the national interests of their peoples.” Controversially, he was a member of the Palestinian National Council, advocating for the establishment of a Palestinian state which would ensure equal political and human rights for the Palestinians in Israel, including the right to return to the homeland. As a public intellectual, he saw his duty as applying analytical concepts to a real world in which there was domination and subjugation by national powers over oppressed and powerless people.

One of Said’s first political acts was to protest the 1967 Six-Day War (5–10 June 1967), in which Israel occupied the Palestinian territories, including the West Bank and Gaza, Syria’s Golan Heights, Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, and parts of southern Lebanon. He went to great lengths to fracture the stereotypes of “the Arab” and to define the cultural and historical realities of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Later, Said defined Zionism—from the standpoint of its victims, including Zionist claims and the right to a Jewish homeland and “the inherent right of national self-determination of the Palestinian people.” Several books penned by Said followed.

Said’s independent membership on the Palestinian National Council (PNC) from 1977-1991 was a critical part of his role as a public intellectual. In that role he was “a proponent of the two-state solution to the Israeli-–Palestinian conflict, and voted for the establishment of the State of Palestine at a meeting of the PNC in Algiers.” However, Said resigned his membership in the PNC as a protest of its internal politics and his opposition to the signing of the Oslo Accords (Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, 1993).

Specifically, Said was opposed to the fact that the Oslo Accords did not produce an independent State of Palestine. Especially troublesome to Said, according to Wikipedia, “was his belief that Yasir Arafat had betrayed the right of return of the Palestinian refugees to their houses and properties in the Green Line territories of pre-1967 Israel and that Arafat ignored the growing political threat of the Israeli settlements in the occupied territories that had been established since the conquest of Palestine in 1967.” How prescient was Said, given today’s situation—another day, another war!

Said’s academic awards are too numerous to list here but a few of his non-academic yet perhaps more historical accomplishments are worth listing. According to literary source, The Forward, “Anwar Sadat wanted him to head the Palestinian delegation at the Geneva peace talks. The Department of State tried to get him to convince the PLO to recognize Israel. He sat on the Palestinian National Council for 14 years and used his clout to push for a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. When he quit the Council in 1993 to protest the Oslo Accords, it was international news.”

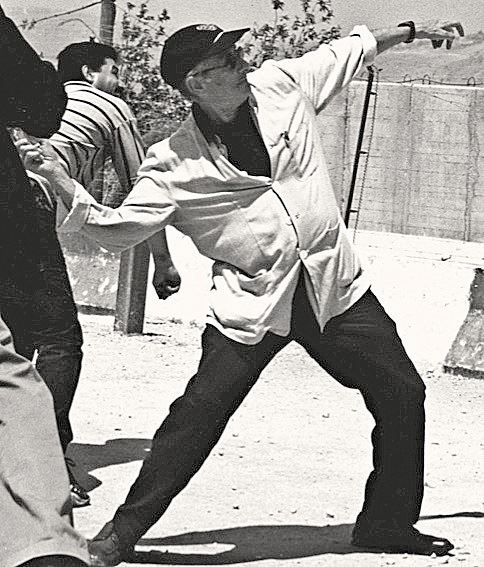

A telling story of role conflict experienced by Said was captured in a photo of him demonstrating his pro-Palestinian, anti-Orientalist sentiments. On 3 July 2000, while he and his father were touring the region, “Said was photographed throwing a stone across the Blue Line Lebanese–Israel border, which image elicited much political criticism about his action demonstrating an inherent, personal sympathy with terrorism; and, in Commentary magazine, the journalist Edward Alexander labeled Said as “The Professor of Terror”, for aggression against Israel.” Said clarified his action, stating, it was “a two-fold action, personal and political; a man-to-man contest-of-skill, between a father and his son, and an Arab man’s gesture of joy at the end of the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon.”

On 24 September 2003, after enduring a 12-year sickness with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Said died, at 67 years of age, in New York City. Said is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Broumana, Jabal Lubnan, Lebanon.

The Arab World, Palestinians, and Arab Americans lost a giant, someone who, notably, could talk the talk and walk the walk.

Sources:

-“Edward Wadie Said,” Wikipedia Bios of Arab Americans 2023

– “Activist, Professor, Politician, Aesthete — the many contradictions of Edward Said,” The Forward, 4/20/2021

John Mason, Ph.D, focuses on Arab culture, society, and history, is the author of LEFT-HANDED IN AN ISLAMIC WORLD: An Anthropologist’s Journey into the Middle East, New Academia Publishing, 2017. He has taught at the University of Libya, Benghazi, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and the American University in Cairo; John served with the United Nations in Tripoli, Libya, and consulted extensively on socioeconomic and political development for USAID and the World Bank in 65 countries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab America.

Check out our Blog here!