Reclaiming Deep Roots: The Arab World’s Revival of Indigenous Heritage

By: Fayzeh Abou Ardat / Arab America Contributing Writer

An interesting cultural change is occurring throughout the Arab world, one that looks not only to Islamic or Arab nationalist identity but also much deeper back to the pre-Islamic and indigenous civilizations that moulded the oldest histories of the region. These ancient cultures, from the Sabaeans of Yemen to the Amazigh of North Africa and the Nabateans of Jordan, are being rediscovered, reinterpreted, and reintegrated into contemporary identity.

This movement is not about renouncing Arabness; rather, it reflects a desire for historical depth, authenticity, and cultural plurality at a moment when many cultures are renegotiating who they are and how they tell their past. Several forces fuel this comeback. Many regimes reconsidered using national identity as a stabilizing strategy in the wake of the Arab Spring. Younger generations, influenced by global connectivity and digital culture, are looking for roots outside of contemporary nation-states and political boundaries. States are investing in legacy as part of soft power, cultural tourism, and nation branding. The consequence is a layered landscape where old symbols, writings, and stories are surfacing in fashion, government, media, and collective memory.

Several forces fuel this comeback. Many regimes reconsidered using national identity as a stabilizing strategy in the wake of the Arab Spring. Younger generations, influenced by global connectivity and digital culture, are looking for roots outside of contemporary nation-states and political boundaries. States are investing in legacy as part of soft power, cultural tourism, and nation branding. The consequence is a layered landscape where old symbols, writings, and stories are surfacing in fashion, government, media, and collective memory.

Nabateans, Amazigh, Phoenicians: A Patchwork of Resurgent Histories

In Jordan and parts of Saudi Arabia, Nabatean heritage has surged to the forefront of national images. Jordan’s identity-making presently revolves around the city of Petra, which has long been a global architectural marvel. The government highlights Nabatean art, water systems, and engineering as distinctively local accomplishments that predate Greco-Roman influence. Saudi Arabia’s AlUla project parallels this, establishing the monarchy as a guardian of Lihyanite, Dadanite, and Nabatean cultures. This shift signals a divergence from the formerly prevalent narrative centred mostly on religious roots.

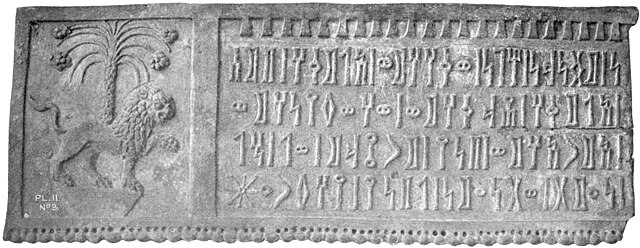

In North Africa, Amazigh identity has undergone a dramatic rebirth. Morocco recognized Tamazight as an official language. While festivals, films, and textbooks highlight Amazigh history as an intrinsic component of national culture. A social movement in Algeria to recognize indigenous roots outside of colonial or Arab nationalist contexts is reflected in the resurgence of interest in individuals such as Jugurtha and Massinissa. The Tifinagh script and traditional tattoo designs are examples of Amazigh symbols. They have gained popularity among young people who view them as marks of continuity and authenticity.

Lebanon’s Phoenician heritage has also revived, but more controversially. In order to support a multicultural, secular national identity, some Lebanese intellectuals place a strong emphasis on Phoenician maritime culture. Opponents contend that it can be utilized politically, but in any case, its resurrection points to a larger regional trend: the inclusion of ancient civilizations in contemporary identity discussions. Even in Yemen and Oman, people are revitalizing interest in Sabaean and Himyarite heritage, often as a source of morale in the midst of violence and disintegration.

Artist Alfred Fredericks, via Wikimedia Commons

Why Now? Politics, Youth Culture, and Decolonizing History

Generational differences are one of the main forces behind this tendency. Arab Gen Z: digitally connected, politically conscious, and culturally experimental, has adopted pre-Islamic and indigenous elements as part of a global rebirth of local identities. Social media sites like TikTok and Instagram have enhanced traditional costumes, poems, rituals, and scripts, changing ancient legacy into a modern aesthetic. This is particularly obvious among the diaspora, where cultural revival intersects with identity preservation and opposition to assimilation.

Another crucial issue is decolonization of knowledge. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Western orientalists shaped the histories of the Middle East and North Africa. By recovering pre-colonial narratives, Arab communities are exercising ownership over their own past. This is not just the case for heritage sites; indigenous civilizations are increasingly being highlighted in classroom curriculum, museum exhibits, and cultural events throughout the region as sources of pride rather than as minor details of Western archaeology.

In terms of politics, states have found these histories helpful in creating inclusive national identities within multiethnic societies. Pre-Islamic heritage provides a neutral, non-sectarian base that can bring together disparate groups. Amazigh culture in Morocco and Sabaean culture in Yemen, for instance, can function as unifying tales that cut beyond linguistic, tribal, and sectarian divides. On the international scene, heritage initiatives like AlUla and the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade in Egypt serve to uphold notions of durability, stability, and cultural sophistication.

A Multi-Layered Identity for the Future

The rebirth of indigenous heritage does not obliterate Arab identity—but it complicates and enhances it. Rather than a monolithic story, the region’s identity is increasingly recognized as a tapestry made from multiple threads. Such as Arab, Islamic, indigenous, colonial, and global. This pluralism offers a powerful counter-narrative to oversimplified Western depictions of the Arab East. It presents new possibilities for cultural diplomacy, academic study, and social cohesiveness.

As these movements expand, they bring up significant issues. Who gets to pick whose history are highlighted? How can states honour indigenous traditions without adopting or politicizing them? And perhaps most importantly: what does it mean to be “Arab” in a region where historic identities are rising with newfound force?

What is obvious is that the Arab world’s deep history is becoming a critical component of its future—and the rediscovery of these ancient civilizations is redefining not only heritage but the very idea of identity in the 21st century.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check our blog here!