Syria's Architecture: Expressions of Culture, History and Climate

By: Ralph I. Hage / Arab America Contributing Writer

Syria’s traditional architecture stands as a rich testament to centuries of cultural continuity, regional adaptation, and environmental intelligence. The country’s strategic location at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, Arabian, and Mesopotamian worlds has fostered a diversity of architectural expressions. Traditional Syrian buildings are not merely functional; they are deeply embedded with cultural values, environmental adaptations, and aesthetic ideals. From the vibrant old city of Damascus to the serene homes of Aleppo, traditional architecture reflects Syria’s identity across space and time.

The Courtyard House: Core of Domestic Life

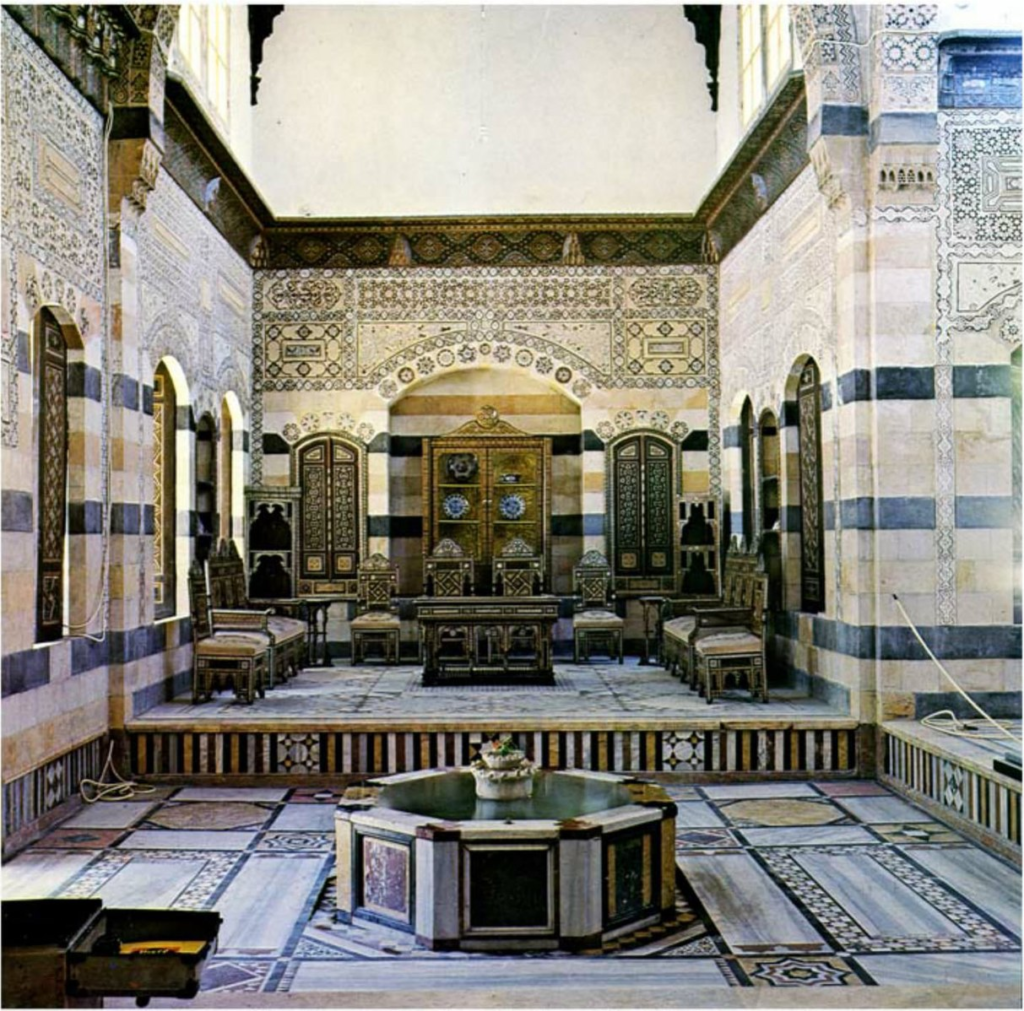

The quintessential element of traditional Syrian architecture is the courtyard house, known locally as a dar. This type of house is designed around a central open courtyard, which functions as the heart of family life. The courtyard creates a microclimate that helps regulate temperature throughout the year–cooling in the summer and warming during the winter.

These courtyards typically feature a fountain, along with vegetation such as citrus trees, jasmine, and roses. Not only do these provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration, but they also offer sensory pleasures that enhance domestic comfort. Rooms are arranged around the courtyard, ensuring maximum privacy from the public street while still encouraging family interaction within.

Architectural Features: Climate, Culture, and Aesthetics

Syria’s traditional architecture employs features that reflect both climatic needs and social customs. These include:

- Iwans: Vaulted semi-open rooms facing the courtyard. Their strategic placement allows cool breezes to flow through, offering relief in hot summers. The use of iwans demonstrates an understanding of natural ventilation systems long before modern HVAC technology.

- Mushrabiyas: Ornamental wooden latticework screens over windows, designed to allow ventilation and visibility from inside while maintaining privacy. These are especially prominent in urban areas like Damascus and serve both functional and symbolic roles.

- Thick Stone Walls: The use of locally quarried stone such as limestone and basalt provides insulation. These thick walls moderate indoor temperatures and reduce the need for artificial heating or cooling. A distinct feature is the alternating use of black and white stone in horizontal bands, known as ablaq masonry.

- Flat Roofs: Often used in the past for sleeping during the hot summer nights, roofs also serve as spaces for drying herbs or as informal family gathering areas. This vertical layering of domestic life reflects the social flexibility built into Syrian homes.

Regional Variations

Despite a shared cultural ethos, traditional architecture varies significantly across Syrian regions due to differences in climate, materials, and local customs:

- Aleppo: Houses in Aleppo are celebrated for their grand design and ornamentation. The use of ablaq masonry is particularly prominent, along with expansive courtyards and detailed wooden ceilings. These homes often include multiple iwans and more intricate floral and geometric stone carvings.

- Damascus: Traditional homes in the capital city often have two courtyards – one for guests and another for family. Homes such as Beit Nizam and Beit Ghazaleh exemplify Damascene architecture, featuring ornate stucco work, wooden mashrabiyas, and calligraphic inscriptions that reflect Islamic artistic traditions.

- Southern Syria (e.g. Hawran): Here, basalt is commonly used due to local geology. Homes are more austere but structurally solid, often consisting of simple cubic forms with few decorative elements. They are built to accommodate seasonal changes and rural lifestyles.

Social Structure and Symbolism

Traditional Syrian homes are carefully designed to respect Islamic social norms, particularly around gender and family structure. The separation between public (Selamlik) and private (Haremlik) spaces is pronounced. The front of the house may include a guest room with a separate entrance, allowing hospitality to be extended without compromising the privacy of the inner family quarters.

This spatial hierarchy reflects deeper cultural values. The courtyard, often featuring an elaborately decorated iwan, serves as a status symbol and an area of ritualized family life. Moreover, the mashrabiya allows women to observe public life without being visible, in line with social norms regarding modesty.

Materials and Construction Techniques

Traditional Syrian architecture is a model of sustainable construction. Builders used locally available materials – stone, wood, lime, and earth – minimizing environmental impact. Lime plaster was often applied to walls for durability and breathability, while wood was reserved for ceilings, doors, and mashrabiyas due to its scarcity in some regions.

Roof beams were traditionally supported by muqarnas or stalactite-like vaults that diffused load and added a decorative element. These architectural choices were not arbitrary; they aligned with the region’s seismic and climatic challenges, showing an impressive understanding of structural resilience.

Decline, War, and Modern Revival

Unfortunately, many of Syria’s historic buildings have been damaged or destroyed due to urban development pressures and, more recently, the recent civil conflict. Cities like Aleppo and Homs have lost significant parts of their architectural heritage due to aerial bombardments and neglect.

Yet there is hope; many Syrian architects and scholars are advocating for rebuilding using traditional design principles. Their vision includes not only restoring buildings but reviving the social and urban fabric that they represent.

Conclusion

The traditional architecture of Syria offers more than historical interest – it represents an intelligent, context-sensitive approach to building that harmonizes with nature and society. Whether through the cooling courtyards of Aleppo, the symbolic iwans of Damascus, or the rugged stone homes of the south, Syria’s architectural legacy lives on.

As the country faces the monumental task of post-conflict reconstruction, looking to these architectural traditions offers a blueprint not just for physical rebuilding, but for cultural renewal as well. Embracing this legacy is not about nostalgia–it is a practical, resilient response rooted in centuries of wisdom.

Ralph Hage is a Lebanese American architect who divides his time between Lebanon and the United States.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!