The Khashokji Mosque of Beirut - Where East Meets West

By: Ralph I. Hage / Arab America Contributing Writer

Tucked beside the greenery of Beirut’s Horsh Park, the Khashokji Mosque is easy to miss at first glance. Modest in size and stripped of the ornamental flourish that defines many traditional mosques, it instead attracts attention through its simple refinements. Designed by Lebanese architect Assem Salam and completed in the early 1980s, the Khashokji Mosque is a thoughtful meditation on what it means to build modern Islamic architecture in a rapidly changing urban and cultural landscape. Rather than echoing historic mosques of Ottoman or Mamluk design, Salam chose to reinterpret Islamic spatial and spiritual values in various ways. These include referencing the past and creating a new architectural language through the use of modern materials and design choices. The result is a building that feels deeply rooted in Lebanese culture.

A Mosque in Two Movements

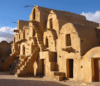

The mosque is divided into two distinct but connected spaces: a closed prayer hall and an adjacent open-air courtyard. The indoor prayer space is a cube clad in sandstone, solid and grounded, anchored by freestanding concrete columns and capped with a sculptural concrete shell roof. This shell is not a dome in the traditional sense, but rather a reinterpretation – referencing both Islamic architectural heritage and the mid-century concrete experiments of Spanish-Mexican engineer Félix Candela. This can be explained by the Lebanese characteristic of adopting a foreign concept and reinterpreting it in a uniquely Lebanese way. The choice of form was not merely stylistic. The dome is more than a formal device; it is a symbol of celestial order and divine unity. But rather than repeating past forms, it was reimagined. The concrete shell above the prayer space carries the symbolic essence of the dome without resorting to replication.

The Outdoors as a Spiritual Space

Adjoining the main prayer hall is an open courtyard, framed by cast concrete arcades and shaded by a flat roof slab punctuated with clerestory openings. This design blurs the boundary between inside and outside. Sunlight filters through these openings, animating the space throughout the day and offering worshippers a sensory connection to the divine that’s both architectural and environmental.

What’s especially striking is the orientation of the arcades. Instead of forming part of the mosque’s façade, they run perpendicular to it – presenting to the street only their slim vertical profiles. This move is subtle but intentional. It sidesteps the expected grandeur of traditional Islamic entrances and instead emphasizes privacy, humility, and inner reflection.

This design move could be analyzed as a literal subversion or redirection of traditional architectural language. It’s not defiance for its own sake, but rather a considered reworking of formal elements to suit a new urban and localized spiritual context. This can also be seen in the subtle detail of the geometric metal roof frame, which references the ceiling ornamentations of traditional Lebanese architecture.

The Minaret as a Modern Marker

The minaret, too, avoids historical replication. It is square in plan, clad in the same warm sandstone as the prayer hall, and rises simply but purposefully. Narrow vertical slits cut through its surface like arrow slits, creating both visual texture and a quiet allusion to fortification.

The minaret anchors the mosque within the urban fabric of Beirut without overwhelming it. The curves of its arches can also be found in traditional Lebanese architecture.

Material Matters

One of the signature features of this mosque is the careful interplay of modern construction techniques and local material traditions. At the Khashokji Mosque, sandstone and concrete speak to both the past and the future. The sandstone connects the building to centuries of Levantine architecture, while the raw, cast-in-place concrete connects it to the architectural innovations of the 20th century.

Architecture as Cultural Conversation

Built between 1974 and 1982 – a period marked by deep political instability and civil war in Lebanon – the mosque is also a product of its time. Rather than retreating into nostalgic revivalism or turning to flashy modernism, its design engages in a dialogue with both.

The Khashokji Mosque doesn’t ask for attention. It doesn’t try to dominate its surroundings or replicate holy models from centuries past. Instead, it listens to the past, to the present, to a constantly evolving national identity, its worshippers’ needs, and more.

In doing so, it challenges common assumptions about what Islamic architecture must look like. It asks: Can modern architecture be spiritual? Can the deceptively simple carry meaning? Can we design with tradition without being bound by it? This structure shows us that the answer is clearly: yes.

An Enduring Legacy

More than four decades after its completion, the Khashokji Mosque continues to offer a unique vision of Islamic architecture – one rooted in history, modesty, and a keen cultural understanding.

Architects and critics looking for examples of meaningful, contemporary religious design would do well to study this modest building in Beirut. It proves that relevance doesn’t require reinvention from scratch, nor blind imitation. Instead, it requires what was practiced here: integrity, cultural awareness, and a willingness to rethink familiar forms with humility and imagination.

Dedicated to the Memory of Rafic Siblini