The King-Crane Commission: Early Arab Self-Determination?

King Crane Commission, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By Liam Nagle / Arab America Contributing Writer

It is 1919. In the wake of the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, there was varied discussion on what was to become of the Middle East. The victorious Allied Powers deliberated on what was to become of the territory. Whereas Britain and France wanted to claim new areas as colonial holdings, the United States instead sought to try to achieve a lasting peace by appealing to the national aspirations of the area’s inhabitants. To aid in this goal, the United States approved sending a commission of inquiry to assess the opinions of the populace in Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Anatolia – which became known as the King-Crane Commission. But given the ensuing decades of British and French colonial rule in the region, it seems that the commission wasn’t able to achieve its goals. What happened with the commission, and why did it fail?

Competing Interests

William Orpen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

To understand the King-Crane Commission, we’ll have to look at the competing interests of the United States, Britain, and France.

A New US Foreign Policy

The United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, was supportive of a set of principles called the Fourteen Points. The goal of the Fourteen Points was to prevent another future conflict by, among other things, catering to the views of the inhabitants of regions affected by the war. New countries could be founded on the basis of self-determination, as Wilson viewed that the First World War was brought about partially due to the suppression of minorities within greater European empires.

By founding new countries on the basis of self-determination, a lasting peace could be achieved – and World War I could really be “the war to end all wars”. However, Wilson had to tread a fine line at home. The United States had adopted an isolationist stance to international affairs ever since its inception – only leaving it to enter the World War. Wilson’s pro-self-determination stance ran contrary to the isolationists at home, who would rather just leave the peace conference to the other powers and return to isolationism.

At Odds With Old Powers

However, these views were contrasted by the British and French – both governments were already firmly supportive of establishing their own colonial authorities in the Middle East. France had a particularly “interesting” relationship with the areas around Syria and Lebanon, with France having intervened numerous times in the area in the 1800s in the name of protecting the Christian populations of those regions.

Britain, meanwhile, was in a complicated position due to its support for several, contradictory post-war agreements. Britain had proclaimed its support for Arab self-rule under Hussein bin Ali, who had started a rebellion against the Ottomans. Simultaneously, Britian had proclaimed its support for British and French domination of the region through the Sykes-Picot Agreement, as well as the creation of a “national home” for Jews in the land of Palestine through the Balfour Declaration. Ultimately, in the post-war climate, Britain’s desire for colonial holdings in the Middle East won out over its support for Arab self-rule.

With the United States pursuing self-determination, while the British and French pursued establishing colonies, their competing views came to a head at the peace conference. The King-Crane Commission, officially known as the 1919 Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey, was proposed by the United States. The U.S.’ proposal would be to bring together the U.S., Britain, France, and Italy to assess the situation and opinions of the post-Ottoman Middle East, and help set the basis for the creation of new states of self-determination there. However, the British, French, and even the Italians opposed this, resulting in the U.S. pursuing the commission on their own.

Findings of the Commission

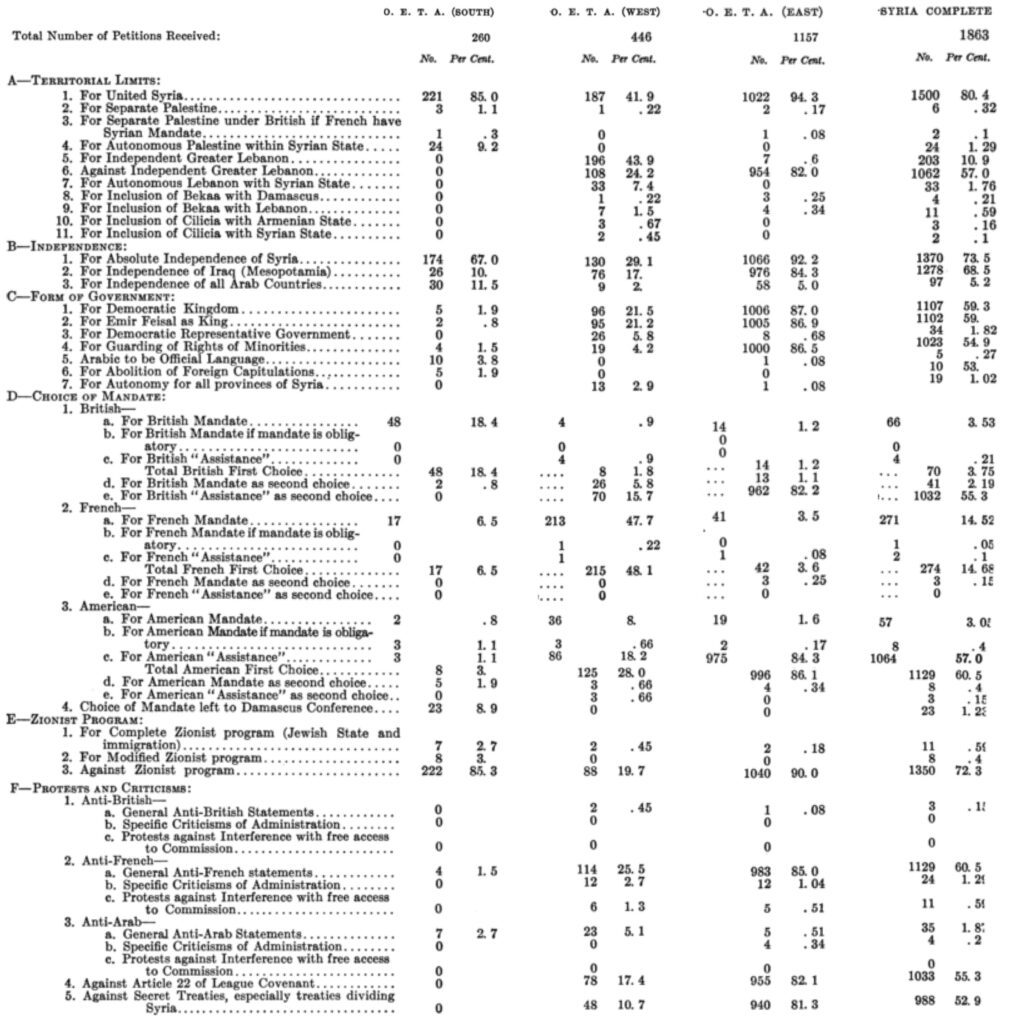

Two representatives were selected for the commission by President Wilson, that being Henry Churchill King and Charles R. Crane. The commission spent 42 days in the Levant area, which they labelled as “Syria” although it encompassed modern-day Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, and gathered the statistics and opinions of the populace. A variety of questions were asked about what the new country would look like, including its territory, independence, form of government, and on Zionism.

Results of the King Crane Commission

The results of the commission were relatively concrete. By far, the majority of the population in the area of “Syria” supported the establishment of a united, Syrian state. Although a majority of the Lebanese population supported an independent Lebanon, the rest of “Syria” largely opposed this and instead supported integrating Lebanon into this Syrian state. Decisions on what form of government this new Syrian state would be differed – the population was evenly split on whether to form a democratic republic, or a monarchy.

Most of the populace also rejected the Zionist project, where Britain was sending Jews to live in Palestine at this time. Interestingly, although the vast majority supported independence, if colonialism was unavoidable, the populace gave their support for a U.S.-led colonial administration over British- or French-led ones. But ultimately, the statistics were relatively clear – those of the “Syria” area supported a unified, independent state. The form of government remained unclear, and the stance on Lebanese independence would be contentious.

The Legacy of the King Crane Commission

The results of the commission, completed in 1919, went largely unheeded – the results of it weren’t even publicly revealed until 1922. Undermined from the very beginning, the British and French governments had already opted to divide the Middle East into spheres of influence. Ironically, Wilson’s attempts at promoting self-determination became justification for British and French imperialism; under the guise of “guiding” the areas to become independent states, the League of Nations established “Mandates” under British and French control.

The United States, meanwhile, withdrew back into isolationism. President Wilson himself, although somewhat successful in achieving his goals for self-determination in Europe, was unable to convince the United States to have an active role in international politics. He would withdraw back to the United States and, that same year, suffer a debilitating stroke that compromised his physical and mental state. He would die five years later in 1924. The King-Crane Commission, an early attempt to promote self-determination in the Middle East, would fail in the wake of colonialism. Its findings nonetheless show the unpopularity of the British and French Mandates, and allude to the eventual independence movements that would shake the post-colonial world.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!