The Lebanese Roots of Surf Rock: Lana Dale Reflects on Her Husband Dick Dale’s Life

By Ralph I. Hage/Arab America Contributing Writer

What do the oud, surfboards, and Stratocasters have in common? The answer: Dick Dale — whose fusion of Arab melody, American rhythm, and electric experimentation continues to reverberate across music and cinema today. With the intention of honoring her husband’s Lebanese heritage, Lana Dale gives a rare, personal look into Dick’s life.

“My music comes from the rhythm of Arab songs. The darbukkah, along with the wailing style of Arab singing, especially the way they use the throat, creates a very powerful force.”

-Dick Dale, 1998 (George Baramki Azar interview)

A Lebanese-Polish Son of Massachusetts

Dick Dale, born Richard Anthony Monsour on May 4, 1937, in Boston, Massachusetts, earned the title of ‘The King of the Surf Guitar’ for his pioneering work in creating the sound that would define surf rock and influence generations of musicians. His early life in Quincy, Massachusetts, was shaped by a deep connection to both his Lebanese and Polish roots. His father, James Monsour, was born in Lebanon, and his mother, Sophia “Fern” Monsour, was of Polish descent. While Dale would later become globally known for his surf guitar mastery, his upbringing was steeped in both Eastern and Western traditions. His uncle, a skilled oud player, introduced him to Middle Eastern music, which would later influence the distinctive scales and melodies in his own compositions.

In addition to his life in Quincy, Dick spent his summers in Whitman, Massachusetts, staying with his grandparents, Tony and Sophia Dansewickz. Despite his heritage often being overlooked in the history of rock music, Dale was proud of his Lebanese background. In interviews, he spoke often about the influence of its culture on his music. According to his wife, Lana Dale, he was connected to his father’s Lebanese roots, which he felt shaped his identity and his approach to music. This connection is especially evident in songs like “Misirlou,” where the use of exotic Arab scales and rhythms sets the tone for much of his early work.

“Dick created his own sound and began his career in 1954 — not in the late 1950s or early 1960s, as many write.”

-Lana Dale, December 2025

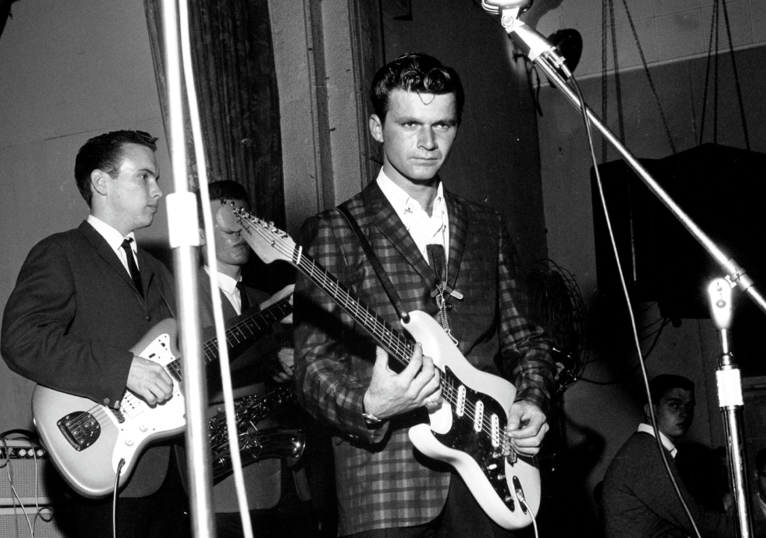

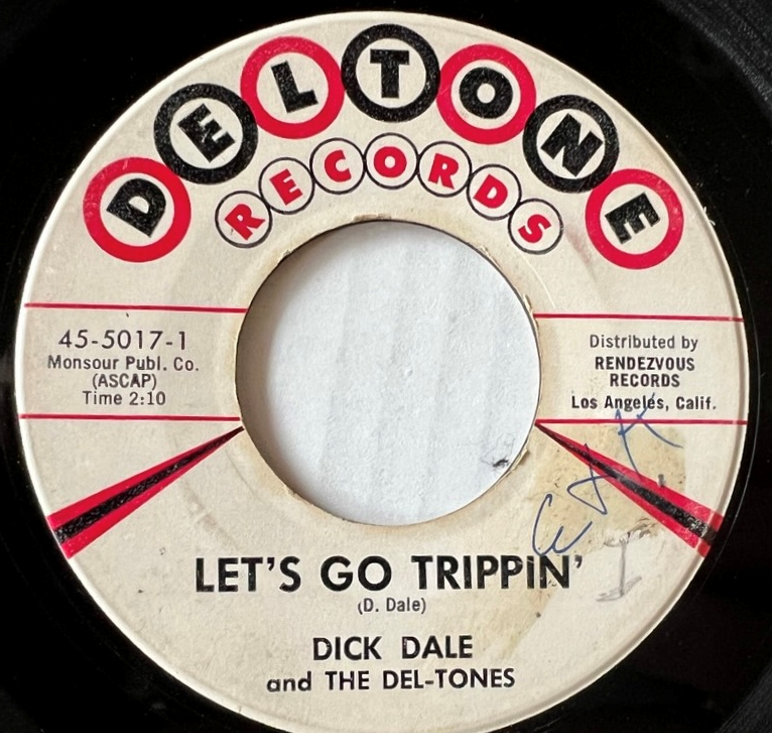

A Career That Began Earlier Than Anyone Realizes

Dick Dale’s musical career began much earlier than most people realize. While surf rock is often associated with the early 1960s, Dale was creating the genre in the mid-1950s. At that time, he began playing at the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa, California, where his band, The Del-Tones, performed for an audience of surfers. His style, marked by fast picking and early experimentation with reverb, contributed to what would later be recognized as the surf-rock sound. Their 1961 track, “Let’s Go Trippin’,” a single frequently cited as the first surf rock song, was later covered by the Beach Boys.

Dale’s early musical influences ranged from jazz to rockabilly, but he became increasingly fascinated with surf culture and the energy of the waves. His desire to capture the power of surfing on the guitar led him to experiment with sound techniques that would later define surf rock. This synthesis reached a peak with one song in particular.

Misirlou, Miserlou

While Dick Dale’s pioneering use of reverb is often praised, it was his ability to blend Western effects with non-Western scales that transformed guitar playing and reshaped rock music. Some later genres, including psychedelic rock and early metal, drew on techniques similar to those Dale helped popularize.

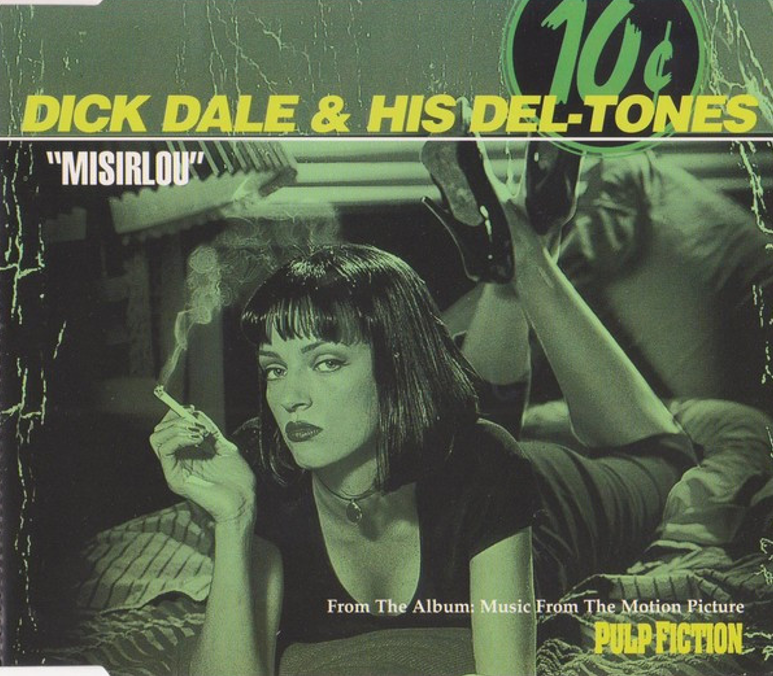

A widely recognized example of this fusion is Dale’s rendition of “Misirlou,” a track that would go on to epitomize the energetic spirit of 1960s rock ‘n’ roll.

“The song ‘Misirlou’ is an Arabic love song… Its title, ‘Misirlou,’ means, ‘The Egyptian.’”

“Yes, on my uncles’ albums, I saw Miserlou spelled as Misirlou… I was learning some songs, applying Gene Krupa’s drumming speed to them and calling it rockabilly. Then this kid… came up to me and said… “Could you play something on your guitar on just one string?’ I thought oh, geez…

“In order to buy myself some time, I told the boy, ‘Come back tomorrow!”

“I realized I could possibly play Misirlou on one string. After plucking out the melody, it sounded a bit boring. I thought, wait a minute, I’ve got to play it with a Gene Krupa-style rhythm. The people who wrote the song are probably rolling over in their grave at my version of it. I played it onstage the next night and the rest is history.“

-Dick Dale, in an interview for The Guitar

It became synonymous with the era of drive-in theaters, diners, and the surf culture that dominated the American West Coast, often evoked in the works of filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino to evoke a sense of nostalgia for that period.

Although Dale made the song famous in America, the exact author remains unknown, as is the case with many traditional folk songs, but by the 1920s, musicians from many Eastern Mediterranean cultures had adopted and reinterpreted it. The earliest known recording is from 1927, performed in the rebetiko style, a unique blend of traditional Greek music, Orthodox chanting, and the Ottoman songs that had been popularized during Greece’s occupation under the Ottoman Empire.

Dale often explained that his version of “Misirlou” was inspired by an Arabic rendition he had heard on the oud, a traditional Arab stringed instrument, and this influence was evident in the song’s fast-paced, dynamic rhythm and exotic scale.

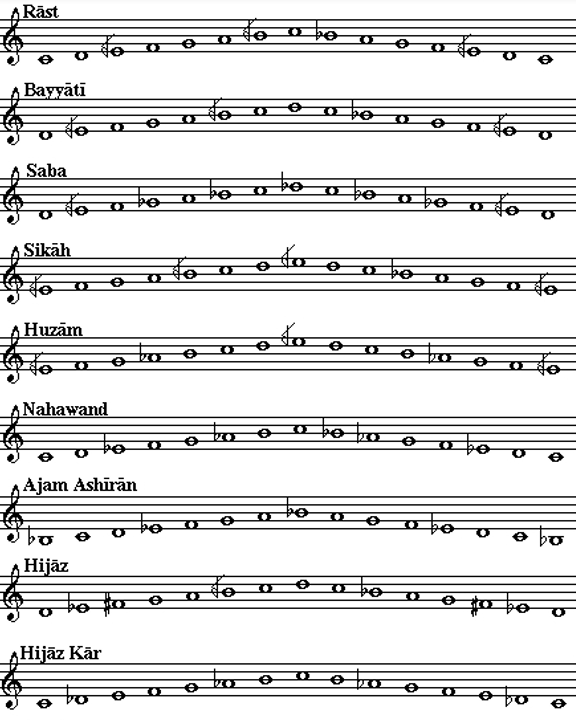

Arabic Maqams: The Roots Beneath the Sound

Dick Dale’s interpretation of “Misirlou” didn’t just rely on speed or electrification — it drew heavily from the Arabic maqams he grew up hearing within his Lebanese household. Maqams, the modal systems of Arab music, use microtones, ornamental phrasing, and emotional pathways that differ from Western major and minor scales.

The melody of ‘Misirlou’ aligns most closely with the Arabic maqam Hijaz, known for its distinctive augmented second interval. Dale absorbed these structures instinctively through his uncle’s oud playing. When he transferred those modal patterns onto the electric guitar — and pushed them to blistering speeds — he created a sound that felt both ancient and shockingly new. His success with this synthesis was also a key factor in shaping his collaborations with the Fender company.

“Dick was like a son to Leo Fender, and the two of them collaborated and pioneered the sound of Fender amplifiers, transformers, Stratocaster guitars, and more.”

-Lana Dale, December 2025

Leo Fender and Dick Dale: The Birth of Loud

Dick’s involvement with Leo Fender was fruitful. Together, they pushed the boundaries of sound, with Dick being central to the creation of the ‘loud’ sound. His collaboration with Fender engineers led to the creation of amplifiers that could deliver the powerful, distorted sound that would define the genre.

Eight Decades

Dale’s impact on music spanned nearly eight decades. His influence is seen in the careers of various musicians across genres. The Beach Boys, Jimi Hendrix, Eddie Van Halen, and even more contemporary guitarists like Jack White and Khruangbin have cited Dale as an influence. His use of fast picking and heavy reverb became a cornerstone not only of surf music but also of the punk and metal scenes. He also made appearances on the silver screen:

“[I]n quite a few films…including Let’s Make Love with Marilyn Monroe, Yves Montand, and Tony Randall. He appeared in several more films including Beach Party, A Swingin’ Affair, Muscle Beach Party, Back to the Beach, and Local Boys.”

-Lana Dale, December 2025

Hollywood, Television, and Commercial Fame

His music became synonymous with the beach party and surf culture of the 1960s. He was a regular of TV and radio notables like Ed Sullivan and Casey Kasem, the Lebanese-American DJ who made Dick a fixture on his shows. His music also appeared in several commercials, and his high-energy performances were featured in early MTV videos, such as “Nitro” in the early 1990s. In 1994, the inclusion of “Misirlou” in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction brought renewed visibility for Dale following a period of being overshadowed by the rise of new genres in the 1970s and ’80s. By the 2010s, he was still performing live at festivals.

A Legacy that Lives On

“Unfortunately, my husband’s precise musical history has not been written accurately over the past seven decades. The web, books, and magazines rarely get it right — there is simply so much to know, and only bits and pieces have managed to make it out there.”

-Lana Dale, December 2025

His musical life is only one part of his story. “At some point, I will be writing a book about Dick Dale’s career,” Lana continued. “Dick always said he had ‘100 Windows of Life’ — and this was just one of them.”

An acoustic version of Misirlou appears on Dale’s 1993 album Tribal Thunder. In an interview with The Guitar, he said that “this [version] is the way Misirlou was originally played.” During that studio session, his bandmates were on break, and he didn’t know he was being recorded. In that unguarded moment, Dale wasn’t the King of Surf Guitar — he was Richard Monsour, the Lebanese-American kid from Boston hearing his uncle’s oud echo through the house. Long before surfboards, Stratocasters, and California stages, there was that sound — one that planted a seed and would go on to help reshape American music forever.

Ralph Hage is an architect and writer whose work explores the intersections of art, architecture, and cultural heritage in Lebanon and across the Arab world.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!