The Traditional Architecture of Jordan: A Cultural and Environmental Legacy

By Ralph I. Hage/Arab America Contributing Writer

Jordan, a nation steeped in millennia of history and cultural exchanges, possesses a rich architectural heritage shaped by its geography, climate, and diverse social history. From the rock-carved city of Petra to the humble stone villages of the highlands, Jordan’s traditional architecture reveals a deep understanding of the environment, the needs of its people, and the aesthetics of its time.

Environmental Adaptation and Material Use

One of the defining characteristics of traditional Jordanian architecture is its deep-rooted responsiveness to the natural environment. The arid climate, with its hot summers and cold winters, dictated construction techniques and material choices. Vernacular buildings were typically made from local materials such as limestone in the highlands, basalt in the north, and sandstone in the southern desert regions. These materials were selected not only for their availability but also for their thermal properties – keeping interiors cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

The architectural design also accounted for climatic conditions. Houses were often built with thick walls and small openings, minimizing solar heat gain and heat loss. Internal courtyards, another prominent feature, allowed for natural ventilation and provided a private, shaded area that served both social and climatic functions. These courtyards often contained water features or greenery, enhancing microclimatic comfort in hot conditions.

Urban Fabric and Social Structure

Traditional Jordanian towns and villages were organically developed, reflecting a communal lifestyle. Settlements were compact and densely built, fostering social interaction and security while preserving agricultural land. In older cities like Salt and Madaba, homes were clustered along narrow, winding streets that responded to the topography rather than imposed a rigid grid. This layout not only followed the contours of the land but also promoted shade and reduced the impact of hot desert winds.

Architecture also mirrored the social hierarchy and cultural norms. The typical Jordanian house, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, consisted of a series of rooms arranged around a central courtyard. The layout was often gender-sensitive, separating public and private spaces, with designated areas for male guests (diwan) and women and children. Privacy was a core architectural principle, and this was manifested through enclosed courtyards, high walls, and minimal external windows.

The Bedouin Influence

While settled architecture characterizes much of urban and rural Jordan, Bedouin traditions also played a significant role in shaping the region’s architectural identity. The nomadic Bedouins of Jordan constructed temporary, transportable dwellings such as the “beit al-sha’ar” or black tent, woven from goat hair. These tents were ingeniously adapted to desert life: their fabric repelled rain and provided insulation, while their modular nature allowed for easy assembly and disassembly.

Although Bedouin architecture was primarily non-permanent, it deeply influenced permanent desert structures. For example, desert castles and fortresses built during the Umayyad period, such as Qasr Amra and Qasr al-Kharanah, incorporated elements of Bedouin living, emphasizing simplicity, ventilation, and functionality.

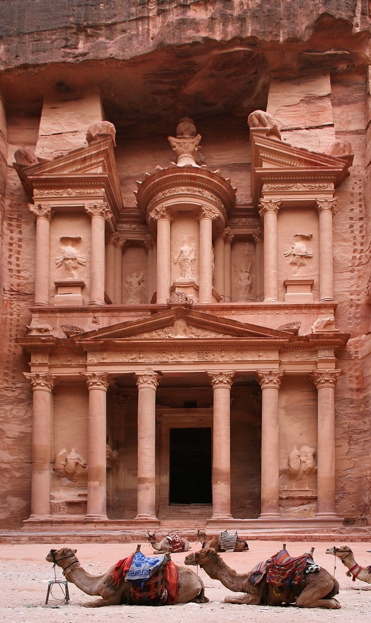

Petra: Monumental Rock-Cut Architecture

Arguably the most iconic example of traditional Jordanian architecture is Petra, the ancient Nabataean city carved into rose-red sandstone cliffs. Dating back to at least the 3rd century BCE, Petra exemplifies a sophisticated blend of Hellenistic and indigenous styles. Its monumental facades – most famously the Treasury – demonstrate advanced engineering skills and artistic finesse, blending Eastern ornamental motifs with Greco-Roman architectural elements such as Corinthian columns and pediments.

Petra’s architecture was not only symbolic but also functional. Tombs, temples, and water management systems were integrated seamlessly into the rock, reflecting an astute understanding of the natural environment. The city’s system of channels, cisterns, and dams allowed the Nabataeans to harvest and store water in an otherwise inhospitable landscape, showcasing an early form of sustainable urban planning.

Ottoman and Early Modern Influences

During the Ottoman period in what is now Jordan (1516–1918), Jordan saw the introduction of new architectural forms, especially in administrative centers and trade hubs. Houses and public buildings from this era – found notably in cities like Salt – feature semi-circular arches, finely carved stone facades, and mashrabiyya screens. These buildings combined Ottoman urban planning with local materials and traditions, leading to a distinctive hybrid style.

In the early 20th century, with the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan, architectural practices began to shift. Imported materials such as cement and steel became more widespread, leading to a gradual decline in traditional building techniques. However, many communities continued to use vernacular methods well into the mid-20th century, especially in rural areas.

Preservation and Revival

In recent decades, there has been a growing awareness of the cultural and ecological value of Jordan’s traditional architecture. Restoration projects in Petra, Umm Qais, and Salt aim to conserve architectural heritage while promoting sustainable tourism. Organizations such as the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (RSCN) have also supported eco-lodges that incorporate traditional construction techniques, such as using mud bricks and local stone, in places like Dana and Ajloun.

Various architects and scholars have also emphasized the relevance of vernacular design in modern construction. By studying passive cooling techniques, spatial layouts, and material use in traditional architecture, contemporary designers in Jordan can create buildings that are more energy-efficient and culturally resonant.

The Traditional Architecture of Jordan

The traditional architecture of Jordan is a testament to the resilience, ingenuity, and cultural depth of its people. It reflects a harmonious relationship between its inhabitants and their environment, shaped over centuries by necessity, belief, and creativity. From the nomadic tents of the Bedouins to the grandeur of Petra and the stone homes of the highlands, Jordan’s architectural legacy offers invaluable lessons for sustainable living and cultural continuity in the modern era.

Ralph Hage is an architect and writer whose work explores the intersections of art, architecture, and cultural heritage in Lebanon and across the Arab world.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!