Where the Stones Remember: Renovation, Reverence, and Reality in Egypt’s Moez Street

By: Laila Mamdouh / Arab America Contributing Writer

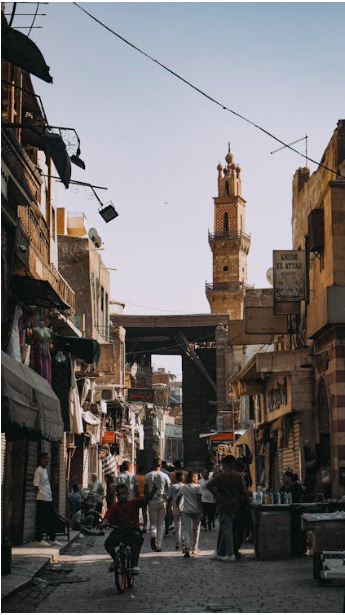

Moez Street, nestled in the heart of Historic Cairo, is a living chronicle of Egypt’s layered past.

Once the core passage of Fatimid grandeur, it embodies over a thousand years of Islamic art,

architecture, and urban life. From intricately carved wooden mashrabiyas to towering minarets,

the street’s aesthetic reflects the intertwined influences of diverse dynasties; Fatimid, Ayyubid,

Mamluk, and Ottoman. Religious and cultural expressions coexist in its mosques, madrasas,

and sabils, making it a vibrant testament to Egypt’s pluralistic heritage.

Walking through Moez Street felt like stepping into a past that is imminent through the stones

and arches, even as modern life surrounds it from every side. The narrow alleys are filled with

school children, shopkeepers, and tourists, all while being encompassed by the minarets and

mashrabiya screens that have seen centuries of Egyptian history. But amid that rich texture of

time, the newly renovated Al-Hakim Mosque stood out as not just striking and pristine, but also

confusing.

There’s no denying that the mosque is beautiful. The white marble glistened under the sun, and

inside, the polished symmetry and cleanliness of the space made it feel peaceful, almost

ethereal. But a part of me couldn’t shake off this strange sense of disconnection. The

renovation, funded and executed by the Dawoodi Bohra community, seemed to, in a way,

deprive the mosque of its historical spirit, its architectural “roughness”, and that imperfect beauty

that makes Fatimid monuments feel alive, historical, and storied.

The Echo of Abu Dhabi: Aesthetic Misplacement

Personally, it reminded me instantly of the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in the UAE: the same

luxurious whiteness, the same silence of perfection. But unlike in Abu Dhabi, here in the heart of

Old Cairo, it felt misplaced. Moez Street is embellished with buildings that tell the evolution of

Islamic art and architecture in Egypt, from the elaborate grandeur of Mamluk design to the

soulful serenity of Sufi shrines. The buildings aren’t just old, but they feel worn in, like a

well-used prayer mat. The aged stone, the calligraphic inscriptions, and the wooden

mashrabiyas extending out from upper windows, all feel grounded in their past. Many of the

structures reflect the four-iwan plan, which was common in Mamluk religious architecture, with

expansive courtyards framed by barrel-vaulted halls.

A Living Heritage: Where History and Humanity Intertwine

What struck me most, though, was how lived-in everything felt. The vibe of how each monument seems stitched into the street, rather than placed with modern precision, is something that amazes me. Locals still occupy spaces next to these monuments; laundry hangs between minarets, and shopkeepers sell sweets and trinkets under the shade of these buildings. That daily life adds a unique vibrancy to the street.

But it’s also a double-edged sword. The encroachment of modern life via carts, wires, signage, and even building additions hinders the historical character. It creates a kind of beautiful chaos: disorganized, noisy, and human. It’s part of what makes Moez Street feel authentic, but at the

same time, it hides the architectural brilliance underneath. You can’t always tell where the monument ends and the market begins. It’s magical yet messy. That rawness seen through the uneven stones and shadowed alleys speaks more loudly than any restoration.

The Bohras’ Vision: Faith and Restoration

In that context, Al-Hakim’s renovation felt a bit like a well-intentioned guest overdressed for a humble gathering. And yet, I was captivated by the story behind it all. Reading the Ahram Online article, explained that for the Bohras, the Al-Hakim Mosque (or Al-Anwar, as they call it) is not just a monument, it’s a spiritual homecoming. Their restoration work carried out with the help of the Egyptian government, was clearly driven by respect for the place rather than pride. Seeing members of the Bohra community gathered there in their ceremonial dress, praying quietly in the newly revived mosque, helped me understand that their vision of beauty, which, despite being different from my own, is rooted in love and legacy for the mosque.

Left Between Awe and Ambiguity

Nonetheless, I kept wondering: Who are these restorations for? As a visitor, I felt both amazed and out of place. The marble floors were so spotless, yet the surrounding area, while historically rich, lacked the infrastructure to make people feel truly welcome. Old Fatimid Cairo, for all its wonder, could be more accessible, more walkable, and frankly, safer. The city has so much to offer if only a little more effort were put into how that offering is presented. In the end, I left feeling both conflicted and inspired. The mosque is undeniably impressive, but it left me with questions rather than answers about authenticity, preservation, and the role of living communities in shaping heritage. I suppose that’s what good history does: it leaves you unsettled just enough to keep looking closer.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter! Check out our blog here!