Arabic or French: Expression in North Africa

By: Diksha Tyagi/Arab America Contributing Writer

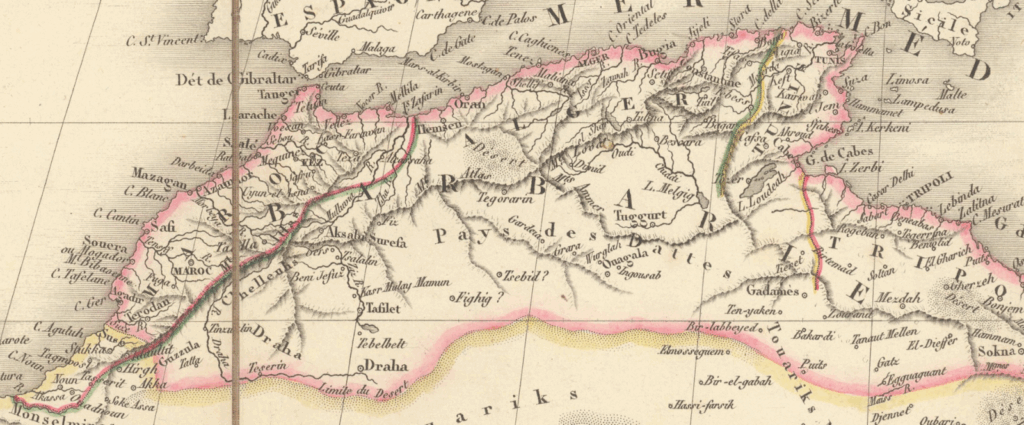

North African authors face a complex and ongoing question. Should one write in Arabic, the region’s historical and national language, or in French, the language of the former colonial administration? Beyond a text’s content, a hidden cultural, political, and historical significance can also be found in the language in which it is written. The Maghreb (the region of North Africa that includes Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia) offers particularly rich perspectives on this enduring dilemma.

Background

The Maghreb’s linguistic landscape is deeply layered. During 7th-century Arab conquests, Arabic was introduced to the region and gradually became the dominant language of administration, education, and religion. At the same time, Amazigh, or Berber, languages, spoken for millennia, retained their importance to regional identity.

The 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed colonial rule establish French as the language of education and government. Though Arabic was still central to cultural and religious life, it was largely excluded from official domains. However, local Arabic dialects and Amazigh languages continued to dominate everyday speech.

After independence in the mid-20th century, Maghrebi governments decided to prioritize Arabization policies to restore cultural and national identity. Modern Standard Arabic became the official language used in schools, media, and government, but French retained its potency in higher education and literary production. Therefore, children often spoke Arabic or regional dialects at home and learned Arabic at school, but still encountered French in professional contexts. Many individuals consequently grew up bilingual, with the necessity of consciously or subconsciously choosing their medium of expression.

Writing in French

Authors often cite practical reasons for writing in French, including broader readership and international recognition, as well as academic comfortability with French after education in French-language schools. Additionally, the syntactical style that French offers may be better suited to certain types of literature. For example, Assia Djebar, an Algerian novelist and scholar, wrote exclusively in French. For her, French allowed her to address themes that might have been constrained by Arabic literary traditions.

At the same time, choosing to write in French comes with historical and cultural implications. Being the language of a former colonizer, its use can reinforce long-standing colonial hierarchies. It can also create distance between the author and local audiences, as many readers in the Maghreb are more comfortable reading Arabic or regional dialects. In this manner, French is a tool for greater flexibility and visibility, but also a source of cultural tension.

Writing in Arabic

Arabic offers authors a medium that is grounded in local history, culture, and identity. Modern Standard Arabic allows authors to connect to their vast literary tradition and assert national and regional authenticity. Yet, Arabic also presents challenges. Standard Arabic differs significantly from spoken dialects, which can make literary works less accessible to certain readers. However, writing in dialectal Arabic, while more familiar to some audiences, may isolate others and additionally lacks prestige in academic contexts.

These tensions can be seen in the works of Algerian authors such as Tahar Wattar and Ahlam Mosteghanemi. Wattar denounced Algerian French-language writers as “vestiges of colonialism”, choosing to write in Arabic. His novels feature colloquial expressions and idiomatic speech to reflect everyday life. Yet, they are still written in Modern Standard Arabic for narrative structure and literary framing. Similarly, Mosteghanemi writes primarily in Modern Standard Arabic but adapts her prose to include cadences of spoken language.

Writing in Amazigh

Beyond Arabic and French, Amazigh languages also are an important component of Maghrebi identity. Amazigh has been gaining recognition in recent decades, with writers and poets incorporating it into their work to assert indigenous heritage. Tahar Wattar, in fact, was one of the first writers to defend the use of the Amazigh language. Some contemporary authors even blend Amazigh, Arabic, and French in the same text, challenging traditional linguistic hierarchies. This approach illustrates the creativity of modern Maghrebi literature, moving past the French-Arabic binary.

Conclusion

Altogether, the choice between Arabic, French, and other regional languages in the Maghreb is far from purely stylistic. Instead, it reflects historical legacies, cultural identity, and considerations of readership and literary opportunity. Contemporary Maghrebi authors navigate these complexities in diverse ways, exemplifying language as both a tool of expression and a space where the region’s past, present, and international connections come together.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!