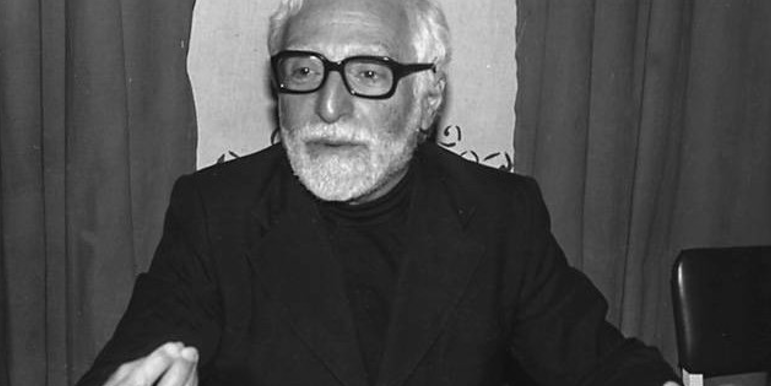

Bishop of the Poor — Grégoire Haddad’s Legacy of Secularism and Social Justice

By Ralph I. Hage/ Arab America Contributing Writer

As the tenth anniversary of Father Grégoire Haddad’s passing approaches, his contributions to social justice, secularism, and interfaith dialogue continue to resonate. His work in Lebanon during a time of political and religious turmoil highlighted his commitment to a society that valued inclusivity and human dignity. While the challenges he faced were great, his approach to social and religious reform remains relevant in a country still grappling with division.

A Life of Rebellion and Reform

Grégoire Haddad, born Nakhle Amine Haddad in Souk El Gharb in 1924, came from a mixed religious background — his father was Protestant, and his mother was Melkite Greek Catholic. He received an education from a variety of religious institutions, which helped shape his later views on faith and society.

Grégoire began studying theology at Saint-Joseph University at a young age. Ordained as a priest in 1949, he quickly became involved in Lebanon’s social movements, aiming to bridge the divide between the country’s diverse religious and political communities.

In the late 1950s, amid Lebanon’s growing sectarian tensions, Haddad founded the Lebanese Mouvement Sociale (Social Movement), a non-sectarian organization that sought peaceful social development and greater solidarity. It was one of Lebanon’s first NGOs and continues to be one of the most active there today. For Father Grégoire, social action was perceived from the perspective of socio-economic development. To this end, he mobilized hundreds of young people, in schools and universities, under the banner of volunteering in the service of the most disadvantaged. He also worked closely with Shi’ite leader Imam Musa al-Sadr to foster Christian-Muslim dialogue, both of whom shared a commitment to reducing sectarian divides and promoting social initiatives.

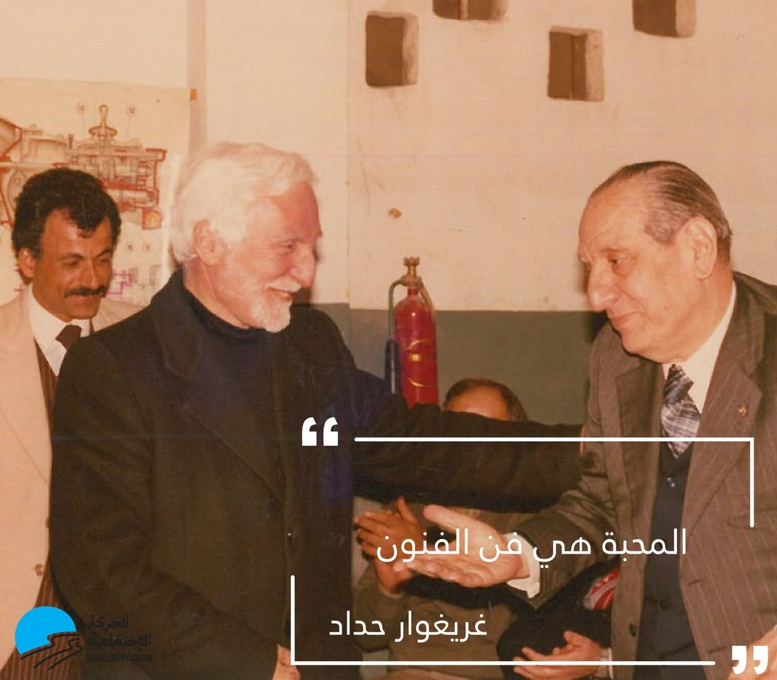

Taken in the context of Lebanon’s sectarian and social challenges, his above phrase — “love is the art of all arts” — reflects the view that social cooperation and human relationships require deliberate effort, much like any practiced craft. It also implies that constructive change depends on cultivating forms of interaction rooted in respect and shared responsibility, rather than in fear or division.

Advocacy for Secularism and Civil Rights

In 1968, he was appointed Melkite Archbishop of Beirut and Jbeil. This was one of the most significant roles within his community — second only to that of the Patriarch — due to the political, social, economic, and religious importance of the diocese.

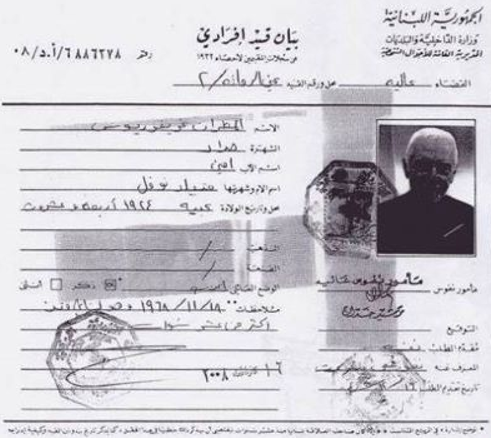

His leadership was marked by his strong advocacy for secularism, particularly the separation of religious influence from civil matters. One of his most notable acts was removing his religious affiliation from his civil records — a bold statement about valuing individuals for their personal qualities, rather than their religious identity. This bold stance earned him the nickname “the Red Bishop,” reflecting his progressive and often controversial views. He was also known as “the Bishop of the Poor.”

“If one is a true Christian, he should be able to accept people as they are, and if people wish to exist in a certain manner, then no one should deter them from doing so, and it is the state’s duty to provide them with the right laws to support their way of living. In the end, if one wishes to cross out their religion, it does not mean that they have lost faith, and a man should be valued because he is man and not because of the belief he practices.”

From an Interview with Gregoire Haddad in 2009

Father Grégoire also supported civil marriage, which put him at odds with many religious authorities who viewed it as a challenge to their power. For him, the core of Christianity was about compassion and respect for the rights of others, regardless of their faith. This stance on civil marriage was part of a larger critique.

Challenging Sectarianism

Throughout his life, Father Grégoire was a vocal critic of Lebanon’s sectarian system. He argued that the country’s political and social issues were rooted in the prioritization of religious identity over merit and competence. His work sought to dismantle the sectarian barriers dividing Lebanese society, advocating for a secular state that would promote equality, merit, and human dignity for all.

In 1974, he began publishing the periodical Afaq (Horizons), which explored the relationship between socialism and Christianity and argued for a more engaged, socially active Church. In these articles, he called for a return to the roots of Christianity, arguing that everything, including religious authority and popular practices, should be open to questioning and debate. His views often put him at odds with both the Greek Catholic Patriarch and other religious leaders. Despite the tensions, he remained steadfast in his belief that social justice and secularism were in line with his Christian ethics.

Later Years and Continued Advocacy

Renowned for his simple and modest lifestyle, he rejected the traditional trappings of the prelacy and even traveled by “service” taxi, despite being the bishop of Beirut. He established parish councils throughout his diocese to encourage greater lay participation in the life of the Church, in accordance with the recommendations of the Second Vatican Council. In this spirit, he introduced a system of free parish services for baptisms, weddings, and funerals, asking only for voluntary contributions from parishioners. These contributions were placed into a communal fund whose proceeds were distributed equally among the parish priests, thereby putting wealthy and impoverished parishes on an equal footing. This avant-garde initiative, however, alienated him from part of the diocesan clergy as well as some of the leading notables of his community.

In 1975, due to political and ecclesiastical tensions, Father Grégoire was pressured to resign as Archbishop of Beirut and Byblos. He was appointed to a titular position in Adana, but he chose not to retire from public life. Instead, he devoted himself to social activism, particularly advocating for secular political reforms.

During the 1990s, as Lebanon faced ongoing political instability, he continued his advocacy, working with secular groups like the Civil Society Movement, which he helped establish in 2000. This movement called for political reforms and sought to strengthen Lebanon’s civil institutions, independent of sectarian and political patronage. His ideas also continue to shape secular and reformist groups, including the Civil Society Movement and political reform initiatives, and they resonated strongly during the October 2019 uprising, when youth and civil society activists mobilized against sectarianism and corruption in pursuit of a more equitable, secular state.

His Legacy

Bishop Grégoire Haddad was undoubtedly one of the most controversial religious figures in Lebanon’s modern history. His distinctive view of social action, his understanding of the role of the clergy, and his revolutionary ideas about living the Christian faith drew widespread criticism. Throughout his career, he was frequently targeted by extensive campaigns of denigration.

“Criticism is nothing new for me. Plus, for me, these criticisms don’t get to me. What is important for me is that my conscience is clear. My Christian conscience finds its peace with secularism — not in sectarianism. Because I’m a bishop and a believer, I am this way.”

From an Interview with Gregoire Haddad in 2009

However, his life was shaped by a vision of a more inclusive, secular Lebanon. He remained committed to the ideals of justice, equality, and dialogue throughout his life, even when facing significant opposition from both religious and political leaders. His work remains a reference point for those seeking to transcend Lebanon’s sectarian divides.

Had Lebanon embraced the voices calling for social empowerment and the dismantling of sectarian systems, it’s impossible not to wonder: where would the country have been today?

Ralph Hage is an architect and writer whose work explores the intersections of art, architecture, and cultural heritage in Lebanon and across the Arab world.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!