Exploring Syria's Ageless Ruins

By: Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer

For a week we had travelled through eastern Syria – from Palmyra to Deir el-Zor and beyond. Our group of four which included myself, my daughter, our guide and driver, had toured a good number of Syria’s desert ruins. Now, we were in Aleppo reposing in the elegant Chahba Cham Palace where we spent the day loafing amid the affluence of the 21st century. Around its luxurious swimming pool, we sipped our drinks and dreamed of the morrow when we intended to explore some of the country’s most important historical remains.

The sun’s rays were barely visible on the horizon when we were driving on the excellent four-lane highway, bordered on both sides by flourishing trees where a few years previously there was only a bare landscape. Beyond, the green fields whose rich red soil has been farmed since the dawn of history, stretched as far as the eye could see. A short distance after passing the town of Saraqab, we were in Tell Mardikh, 64 km (40 mi) south of Aleppo, where the ruins of Ebla are located.

One of the most prestigious archaeological discoveries in Syria, this ancient city, now only an imposing mound, once covered an area of some 56 ha (138 ac). It flourished between 2500 and 1600 B.C. and had an estimated population of 22,000. In 1975, Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome unearthed in its ruins a 17,000-tablet library, filled with new historical material.

These earliest written records in Syria confirm that Ebla was at one time a prosperous city and the capital of a large kingdom whose people spoke Eblan – the ancestor of the Canaanite language. Most of the tablets, housed in the Aleppo Museum and National Museum in Damascus, are being slowly deciphered. Only about 10% of the ruins have been excavated. To amateur archaeologists like ourselves it appeared that the work has only begun.

Back on the Damascus express-way we travelled through a countryside dotted with countless tells. According to a Syrian historian there are over 3,000 of these long forgotten covered towns – thriving cities in ancient times.

It seemed that every village we passed was being transformed, with new construction, edging ever closer to the highway. In between towns and over the tells newly planted orchards amid fields of grain, olives, pistachio and vegetables gave the land an aura of richness with a historic tinge.

At Khan Sheikhoun, we turned westward and drove for half an hour to the ruins of Apamea – once a metropolis of 300,000 where Antony and Cleopatra at one time dallied. Seleucus who named it in honour of his wife Apamea laid its basis in 300 B.C.

In its days of greatness, during the Greek and Roman periods, it was noted for its philosopher sons and was one of the richest and most majestic towns in the world. In times of strife, it could field some 600 war elephants. During the early Christian era, it became a centre of monophysitism – the doctrine denying the duality of Christ. In the subsequent centuries, the city declined until two earthquakes demolished it in 1157 and 1170 A.D.

In the last decade, with funds provided by the entrepreneur and philanthropist, Dr. Osman Aidi – president of the luxury chain, Cham Palace Hotels – the city is again rising from the long-forgotten ruins. With the money supplied by Dr. Aidi, Apamea is rising like a phoenix from its centuries of slumber.

Passing Qalaat al-Mudiq (Castle of the Defile), fought over by Crusaders and Muslims for several centuries, we entered the colourful Ghab valley, sparkling green with vegetation, flourishing on the reddish soil, before continuing on our way northward across this once unhealthy malaria-filled marshland. In the 1960s and 70s the swamps were drained and a series of canals built. Today, this former water-logged land has become one of the richest agricultural areas in Syria.

Passing through the Syrian coastal mountains, lush with green vegetation, we were soon in Latakia, Syria’s main seaport and settled in at the Côte D’Azur de Cham Hotel. We were delighted with our room that opened onto the white sands lapped by the blue Mediterranean waters. In its opulent atmosphere, we rested well that night. Next morning, after a hearty breakfast in the splendid seaside Meridien Hotel, we drove the few kilometres to Ras Shamra or as it was known in historic times, Ugarit.

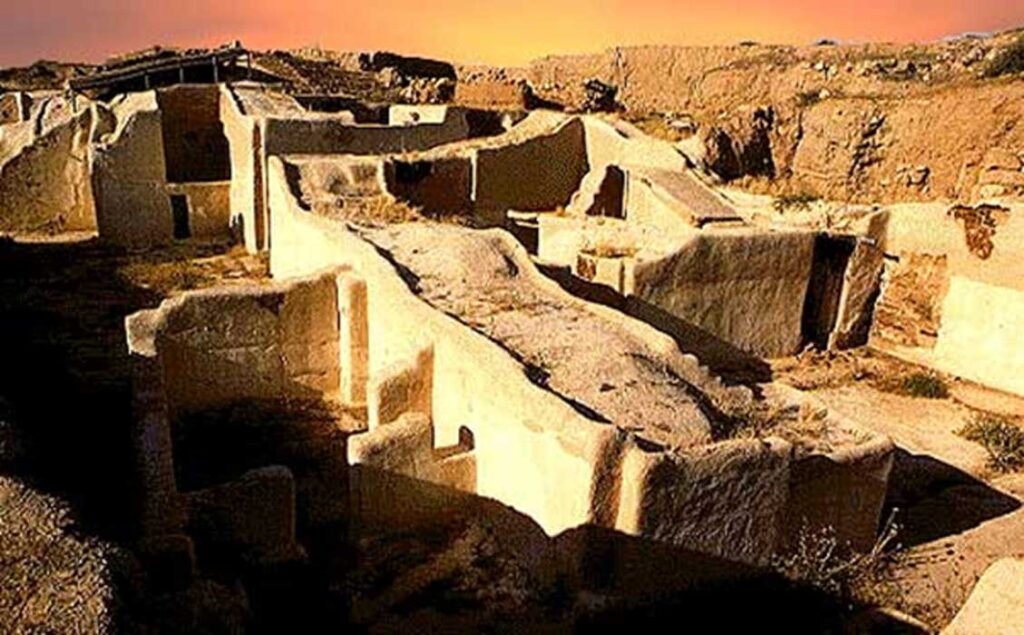

For centuries this capital of a Syro-Phoenician kingdom was lost in history until parts of it were excavated early in the 1930s. From these diggings it was discovered that in the 15th century B.C. the first alphabet, which was the forerunner of all the world’s alphabets, was created. One of the most important discoveries of mankind, it came into common use between the 16th and 13th centuries B.C. and is the mother of Greek and Latin.

From that once influential city, which today appears to be only a heap of stones, there has been excavated the outline of a 90-room palace, a well-preserved grave, parts of temples and stone bases of a great number of buildings.

After Ugarit, we drove along the Syrian coast on a super highway through citrus orchards overshadowed by mountains in which are snuggled Crusaders’ castles. At the seacoast town of Tartous, one of the last cities to be lost by the Crusaders, we turned inland.

Our path took us through mountains covered with olive trees, amid which were nestled, neat, clean villages. To us, the countryside with its superb towns appeared to be a part of southern Europe. Near the fortress of Misyaf, at one time the headquarters of the infamous assassins, we turned eastward and made our way to Hama – noted for its enormous waterwheels, as old as the city itself.

When we checked into the Apamea Cham Palace at Hama, I thought we had entered the fabulous world of the Arabian Nights. Exquisite marble like columns, arches and fountains, designed to fit into the 20th century atmosphere, gave this ultra-modern abode, with a touch of the past, an enchanted aura.

Standing on my room’s balcony, I gazed down on the ancient waterwheels of Hama which for centuries have lifted the waters of the Orontes River to irrigate the surrounding gardens and orchards. It was as if the comforts of the modern age and the relics from Syria’s past had become intertwined, giving the visitor a feeling of tourist contentment.