Lebanon-Land of Hope, Peril, & Refuge-Rich Diversity That Shaped a Nation

In recognition of Lebanon’s Independence Day, we are pleased to present this special long-form feature by Ralph Hage — a sweeping narrative of the many communities that have shaped Lebanon across millennia. From the biblical landscapes of Saida and Tyre to the monasteries, mosques, synagogues, and mountain sanctuaries that sheltered generations, Lebanon emerges as a land defined not by a single story, but by the convergence of many. This essay invites readers to rediscover Lebanon as a refuge, a crossroads of civilizations, and a testament to plurality even in times of struggle. In celebrating independence, we also honor the diverse peoples who built and preserved the idea of Lebanon itself.

By: Ralph I. Hage / Arab America Contributing Writer

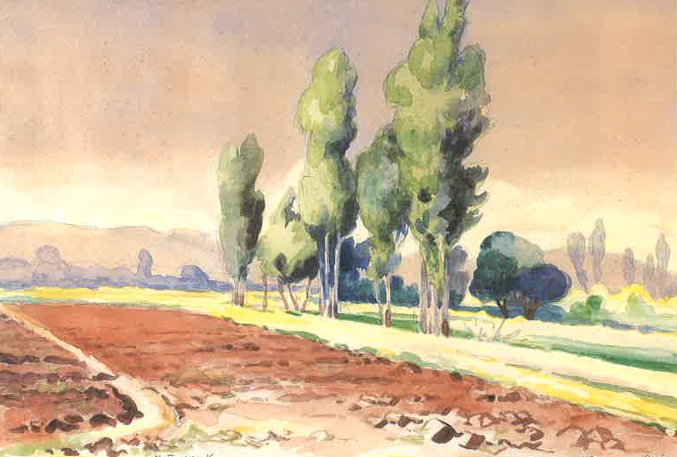

By Moustafa Farroukh, 1950 – Wikimedia Commons

I recently visited the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. It was a sight to behold — filled with beauty, resonating with spirituality, and a sense of stillness. Yet what lingered with me was a much smaller, more modest space tucked within the vast basilica: the Chapel of Our Lady of Lebanon.

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception,

Washington DC

The chapel’s quiet simplicity and humble proportions stood in striking contrast to the surrounding opulence. It reminded me that Lebanon, though wounded today, holds an immense and ancient story — one carried by its many communities, each preserving its own traditions while contributing to a shared identity. Whether large or small in number, every group has shaped Lebanon in essential ways. No community stands alone in the story of this country. But before turning to some of Lebanon’s present challenges, it is important to begin where its identity first took root: in the deep, biblical, and historical soil of the land itself.

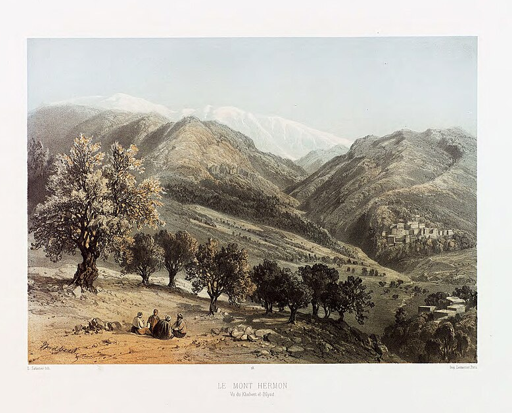

Lebanon In The Bible

Lebanon is mentioned seventy-one times in the Old Testament. It’s cedars (Cedrus Libani) were highly prized in ancient times with King David having used in it building his palace (2 Sam 5:11; 1 Chr 17:1), and King Solomon having used it in the construction of the temple and a palace for himself (2 Chr 2:3-8). It is also one of the few countries where Jesus visited. His first public miracle – where he turned water into wine (or grape juice depending on who you ask) – took place in Qana, which many historians believe is located in modern day Qana, in the South of Lebanon. The second miracle is the healing of the Canaanite woman’s daughter, as recorded by St. Mark (7:24–30) and St. Matthew (15:21–28) in the territories of Sidon and Sour (Tyre), which still hold the same names today. These areas notably represent one of Jesus’ few ventures into non-Jewish majority areas (Matthew 15:21; Mark 7:31). The historical significance of Lebanon doesn’t end with its mention in sacred texts; it extends to the development of Christianity in the region, which began with the early followers of Jesus and has shaped Lebanese culture for centuries.

The Maronites of Lebanon

I love you my brother whoever you are, whether you kneel in your church, worship in your temple, or pray in your mosque.

– Gibran Kahlil Gibran

The presence of Christianity in Lebanon began with Jesus’s visit and spread in the following centuries. The recognized Christian sects present today include the the Maronites, the Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholics, Armenian Catholics, Armenian Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Syriac Catholics, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Copts, Evangelical Protestants, and Roman Catholics. Lebanon has produced at least 21 Saints and 5 Blesseds.

One of the largest Christian denominations are the Maronites who derive their name from Maron, a 4th-century Syriac Christian hermit monk in the Taurus Mountains whose followers, after his death, founded a religious Christian movement that eventually became known as the Maronite Church. Starting in 402 CE, Maron’s first disciple, Abraham of Cyrrhus, set out to convert Phoenician polytheists in the coastal cities and mountains of Lebanon. In this period, the Maronites confined themselves mainly to the mountains of Lebanon in order to avoid persecution from various successive colonial empires. Physical traces of this practice can be found in places like the Qadisha Valley where cave churches were carved into cliff sides.

In the following centuries, the Maronite community grew in size and influence. During the papacy of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585), efforts were made in to bring the Maronites closer to Rome with the Maronite College in Rome (Pontificio Collegio dei Maroniti) being founded in 1584. In his travels through Lebanon in 1832-1833, French author and statesman Alphonse de Lamartine describes the Maronite monks as men who lived simply in addition to possessing wooden staffs and golden hearts.

By the early 1900s, the seed of Lebanese nationalism was reaching fruition and the Maronites played a significant part in the formation of the modern state of Lebanon when the Lebanese delegation led by Maronite Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek presented the Lebanese aspirations for statehood in a memorandum to the Paris Peace Conference on the 27th of October, 1919. Greater Lebanon was declared on the 1st of September 1920, and Lebanese Independence was declared on 22 November 1943.

Famine during World War, the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war and the Lebanese Civil War between 1975 and 1990 greatly decreased their numbers in the Levant. As a result, many emigrated abroad, with substantial diaspora presence in the Americas, Europe, Australia, and Africa. Today, the Maronites continue to play a crucial role in Lebanese society in Lebanese and abroad. Today, they are estimated to make up about 21 percent of the population in Lebanon.

The second largest group of Christians in Lebanon are the Orthodox Christians which are estimated to make up about 8 percent of the population in Lebanon.

The Orthodox Christians of Lebanon

How much more infinite a sea is man? Be not so childish as to measure him from head to foot and think you have found his borders.

–Mikhail Naimy, The Book of Mirdad

The Orthodox Christian community in Lebanon, primarily part of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, is one of the oldest Christian communities in the world. Their presence in Lebanon dates back to the early centuries of Christianity, and today they are concentrated in the northern regions (Akkar, Tripoli, Zgharta) and the Mount Lebanon range, as well as parts of Beirut.

During the Ottoman era, Orthodox Christians were part of the millet system, which allowed them religious and social autonomy. This helped foster a strong community with its own schools, churches, and leadership. In the 19th century, the Orthodox community grew through educational and missionary activities, and many intellectuals, including renowned writer Mikhail Naimy, emerged from this group. They were also key players in shaping Lebanese national identity and contributing to Lebanon’s cultural and intellectual life.

With the establishment of Lebanon’s independence in 1943, the Orthodox Christians were integrated into the sectarian-based political system, which granted them significant influence, including representation in parliament and government positions. However, the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) led to significant migration, with many Orthodox Christians fleeing to countries like France, Canada, and the U.S. Today, the Orthodox Christian population in Lebanon is estimated at around 300,000–400,000, making up about 8-10% of the total population.

Despite the challenges of war and migration, the Orthodox Christian community in Lebanon continues to thrive. They maintain strong religious traditions through churches and monasteries, while also preserving their cultural heritage. Beyond their religious heritage, the Orthodox played an important role in the Nahda, producing thinkers who shaped modern Arabic literature and philosophy. The Orthodox community continues to play a role in advocating for unity, tolerance, and stability, reflecting Lebanon’s pluralistic traditions.

The rest of the Christian minorities, which include Armenians, Melkite Catholics, Protestants, Chaldean Catholics, among others, are estimated to make up about 6.5% of the population in Lebanon and can be found distributed all throughout the Lebanese territory. And just as Christianity has had a profound influence on Lebanon’s heritage, so too has the Shia Muslim community.

The Shia Muslims of Lebanon

“We thank you, God, our Lord, for that you have blessed us with your care,

You brought us together with your guidance, you united our hearts with your love and mercy.

And here we meet in your hands, in one of your homes, and in times of fasting for your sake.”

–Imam Musa Al Sadr, from a speech given in commemoration for the Easter Fast in the Saint Louis Cathedral of the Capuchin Fathers, Beirut, Lebanon – February 18th, 1975

The Shia Muslim community in South Lebanon is one of the oldest in the region and is part of the four main recognized Muslim groups, alongside Sunnis, Alawites, and Ismailis. Local Shia tradition traces the community’s origins to early Islamic history, with some linking it to figures like Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, a Companion of the Prophet Muhammad, and the early followers of Imam Ali. However, historical evidence points to the 9th century CE as the period when the Shia community began to flourish in Jabal Amel, where they established a strong tradition of scholarship and religious learning.

Over the centuries, the size and influence of the community fluctuated due to a combination of religious persecution and shifting political circumstances. Under Ottoman rule, Shia Muslims were often marginalized and placed under Sunni Hanafi jurisdiction. In the 13th century, the Mamluks carried out a series of campaigns to expel Shia populations from areas like Jabal Keserwan, which further strained the community’s growth.

The 11th century, however, saw a significant increase in the Shia population of Jabal Amel, largely due to the migration of Shia families from Kesserwan. This period also saw the rise of influential scholars like Shams al-Din Muhammad ibn Makki, who founded a school in Jabal Amel and contributed extensively to Islamic jurisprudence. Later figures such as Nur al-Din Karaki Ameli and Baha al-Din al-Amili also played crucial roles in shaping the intellectual and religious direction of the Shia community, with some scholars migrating to Persia during the Safavid era to help solidify Shi’ism as the state religion there.

Despite their religious and intellectual contributions, Shia Muslims continued to face significant challenges under Ottoman rule. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many Shia scholars traveled to centers of learning such as Najaf in Iraq to deepen their religious education. In 1884, the first modern school in a Shia-majority area was founded, signaling the beginning of a shift toward modern education. Later, in 1909, Ahmed Aref El-Zein founded Al-Irfan, a journal that became a major platform for the exploration of social, moral, and intellectual issues in the region.

The establishment of the State of Greater Lebanon in 1920 marked a turning point for the Shia community. From that moment onward, the Shia moved from a position of political and economic marginalization to one of greater influence and contribution within Lebanese society. This transformation helped shape the development of modern Lebanon, with the Shia community becoming a key force in its political and cultural landscape.

Today, they are estimated to make up around 28.4% of the Lebanese population with significant diaspora populations in the Africa continent, Iraq and Iran. Alongside the Shia community, the Sunni Muslims have played a central role in Lebanon’s sociopolitical fabric.

The Sunni Muslims of Lebanon

“I tolerate every thought, even if it contradicts what I believe, even if it is a destructive thought. I care about the thought for its own sake, from whatever source. There is no spring without winter, nor the splendor of flowers without a storm.”

–Sheikh Abdallah Al-Alayli

The Sunnis of Lebanon have a presence in the region dating back to the Muslim conquest of the Levant between the years 634 and 638 CE. The Muslim Arab armies marched onto Beirut, Sidon, Jbeil, Baalbek and the Beqaa, while Tripoli was conquered between the years 639 and 640 CE.

Like all of Lebanon’s religious groups, their history was shaped by the historical forces at work in the region. The regions that make up the modern Lebanese state were, for most of Arab Islamic history, sections of the areas ruled by the Sultan or Caliph, whether in Baghdad, Istanbul or elsewhere. An exception might be during the Fatimid rule which came before the Levantine Crusades, after which, the Sunnis returned to their previous relationships with the authorities during the Ayyubid dynasty and Mamluk Sultanate rule, continuing all the way through the Ottoman Empire era. Lebanese Sunnis fared relatively better under the rule of the Ottoman Empire than did the other religious sects in Lebanon. Although the Ottomans ruled loosely, Sunnis in the coastal cities assumed a degree of privileged status which ended with the French mandate.

Initially many of the Lebanese Sunni Muslims, especially among the rural and urban classes, did not wish to be separated from the Sunni community of neighbouring Syria upon the declaration of Greater Lebanon in 1920. Eventually however, many within the Sunni community, including the influential Sunni merchant families of Beirut, supported the National Pact of 1943 since they shared the collective vision of a liberal Lebanese mercantile republic.

The Sunni community in Lebanon produced a multitude of historical and influential figures such as Abdallah al-Alayli, intellectual and author, Abulfattah Al-Zoubi who was a jurist and writer, Muhammad ibn Khalil al-Qawuqji, who was a renowned scholar, preacher and jurist, as well as Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq who was a foundational figure in modern Arabic literature.

Today, they are estimated at the number 28.7 percent of the Lebanese population and are concentrated in Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli, and in the outskirts of the Akkar and the central Beqaa region. They have significant diaspora presence in the nearby Gulf Countries where many reside there for work.

Not to be overlooked, the Druze community, which has its origins in Ismaili Shi’ism, represents another significant minority in Lebanon, adding to the rich tapestry of religious diversity.

The Druze of Lebanon

The true human nature Is gentle and divine, and if the heart is inhabited by the wisdom of goodness, it will become a shining light, and the mind is God’s gift in his creation to distinguish between good and evil, right and wrong.

–Sheikh Abu Hassan Aref Halawi

The Druze faith finds its birthplace in Egypt as an offshoot of Ismaʿili Shiʿism during the reign of the sixth Fāṭimid caliph, al-Ḥakim bi Amr Allah who ruled from 996–1021. Certain Isma’ili theologians instigated a movement proclaiming al-Ḥakim to be a divine figure. This idea was judged as heresy by the Faṭimid religious establishment, who held that al-Ḥakim and his predecessors were divinely chosen, but were not themselves divine. In 1017, the doctrine was preached publicly for the first time, causing unrest in Cairo.

Within this emerging movement, there were two main proponents of the doctrine, Ḥamzah ibn ʿAli ibn Aḥmad al-Zuzani and Muḥammad al-Darazi. Hamzah seems to have been favoured by al-Hakim, with al-Darazi eventually being declared an outcast and disappearing. In spite of al-Darazis disappearance, many continued to use his name as a reference to the faith.

The Druze community gradually vanished in Egypt but found a home in isolated areas of Lebanon of Syria, where their proponents established significant communities. Al-Muqtana retreated from public life in 1037 but continued to write letters expounding Druze doctrine until 1043. It was at that time that the Druze faith closed itself off to the outer world.

Today, the Chouf mountains of Lebanon are home to the world’s second largest Druze population. The center of Druze spiritual life is found in the Chouf Mountains Lebanon, where the Sheikh Al-Aql, their spiritual leader, has his base.

The Druze faith is a monotheistic and Abraham religion whose main canons proclaim the unity of God, reincarnation, and the eternal nature of the soul. Most of their religious practices are kept secret, they do not permit non-Druze to convert into the Druze faith, and as a result, marriage outside their faith is strongly discouraged.

The Epistles of Wisdom are the foundational and central texts of the faith. The Druze faith finds its origins in Ismaíli Shi’ism, and was influenced by various other religions including, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Pythagoreanism, and Neoplatonism, among other philosophies and beliefs. This led to a unique and secretive doctrine based on esoteric readings of various scriptures, which emphasises truthfulness and the role of the mind in distinguishing between good, evil, right, and wrong. The Druze believe in reincarnation and theophany. Today, they are estimated to make up around 5.2% of the Lebanese population.

Culturally, the Druze have contributed deeply to Lebanon’s traditions of learning, ethics, and community life, preserving a heritage rooted in wisdom and scholarship. Their emphasis on education and oral history shaped the character of the Chouf and left a lasting mark on Lebanon’s cultural landscape.

While the Druze community thrived in Lebanon for centuries, another religious group, the Jewish community, also made their home in Lebanon, with a history rooted deeply in several regions of the country.

The Jews of Lebanon

“It is very important for people to know: A Lebanese is a Lebanese. No matter where he goes, he will never forget his country.“

–Anonymous Jewish Lebanese Man Living In New York

The Jewish presence in Lebanon dates back to biblical times. Local legends suggest that the shores of Jiyeh were where the Prophet Jonah landed after being swallowed by the whale. Historically, Jews lived in Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli, Deir Al-Qamar, and other towns. In the first century AD, King Herod built a temple in Sour for the Jewish community, and by the sixth century, synagogues had been established in Tripoli and Beirut.

The community flourished during the 18th and 19th centuries, with many Jews immigrating from Greece, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, settling in Lebanon due to its status as a safe haven. The Lebanese Jewish community grew after 1948, making it the only Jewish community in the Arab world to do so. Jews integrated fully into Lebanese society, contributing to the country’s pluralistic identity and holding positions in the army and internal security forces. They also established schools, including the Talmud-Torah Selim Tarrab School and the Alliance Israélite Universelle School in Beirut.

However, the exodus of Lebanese Jews began in 1958 and continued through several wars. Today, estimates suggest that only 100-500 Jews remain in Lebanon, though some reports indicate the number could be as low as 100. Despite this, the Lebanese Jewish diaspora thrives worldwide, particularly in places like the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and France. In Brooklyn, several synagogues continue the practice of Judaism with a Lebanese influence.

The distinct religious communities in Lebanon are not only defined by their beliefs and practices but also by the sacred sites that have become symbols of their spiritual and cultural heritage.

Sites of Pilgrimage

The historical presence of the different religious groups in Lebanon can be documented through the various sites of pilgrimage located throughout the country.

In 1867, American Author Mark Twain visited Lebanon. He stopped by the town of Karak Nuh, a village in the Beqaa Valley which is famous for claiming the burial site of Noah, the Abrahamic patriarch. In his 1869 book, The Innocents Abroad, he wrote:

“Noah’s tomb is built of stone, and is covered with a long stone building. Bucksheesh let us in. The building had to be long, because the grave of the honored old navigator is two hundred and ten feet long itself! It is only about four feet high, though. He must have cast a shadow like a lightning-rod. The proof that this is the genuine spot where Noah was buried can only be doubted by uncommonly incredulous people. The evidence is pretty straight. Shem, the son of Noah, was present at the burial, and showed the place to his descendants, who transmitted the knowledge to their descendants, and the lineal descendants of these introduced themselves to us to-day. It was pleasant to make the acquaintance of members of so respectable a family. It was a thing to be proud of. It was the next thing to being acquainted with Noah himself.”

About a century later, in 1963, American Jazz musician Duke Ellington visited Lebanon to play at the Casino Du Liban with his orchestra. During his time there, he visited the Our Lady of Lebanon Shrine in Mount Harissa and was left with such a strong impression that he composed and dedicated a song to her on his 1967 album, Far East Suite. The Shrine was built in 1904 in honor of Mary, mother of Jesus, and is highlighted by a large, 15-ton bronze statue.On its base lies the chapel, around which a walking trail winds around the exterior towards the main statue of the Virgin Mary which stands at about 28 feet tall, and has a diameter of about 17 feet meters. The shrine draws in millions of visitors of all faiths every year.

Another inconspicuous site in Sidon is the tomb of Zebulon, who was the tenth son of Jacob, and the founder of one the twelve tribes of Israel. It is still a pilgrimage site for Lebanese Jews today.

The Khalwat al-Bayada is the main sanctuary and theological school of the Druze sect. It is located near Hasbaya in Lebanon and was founded in the 19th century by Sheikh Hamad Kais. It features a large, circular stone bench which sits to an ancient oak tree known as the ‘Areopagus of the Elders’ which is isolated the trees in nature. The Khalwat provides around forty hermitages for Al-ʻuqqāl (the initiated Druze) at various times throughout the year.

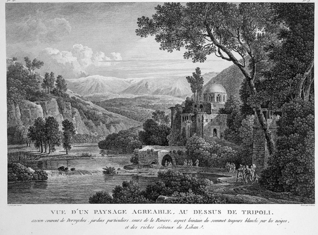

Etching by van de Velde – Hage Family Archives

While Lebanon’s religious landmarks offer a window into its ancient and diverse past, the modern-day significance of Lebanon as a refuge for the displaced adds a profound layer to its identity, one that continues to shape the nation’s role on the global stage.

Lebanon, the Refuge

Left to Right: Sheikh Najib Qubaissi, Sheikh Ahmed Al-Zain, Bishop George Haddad, Bishop Boulos Al-Khouri, Athanasius Al-Shaer, and Imam Mousa Al Sadr – Wikimedia Commons

“Lebanon cannot be abandoned in solitude… For more than 100 years, Lebanon has been a country of hope. Even in the darkest periods of its history, the Lebanese people have maintained their faith in God and have shown the ability to make their country a place of tolerance, respect and coexistence…”

-Pope Francis, 2020

Lebanon’s story is not simply the story of its mountains, its valleys, or its famous cedars. It is the story of the peoples who sought shelter in those mountains, who carved homes into cliffs, built homes, monasteries, mosques, and synagogues, and wove their memories into the land. Each community, carrying its own wounds, and wisdom, helped shape a nation that has long stood as a haven in a turbulent region. Over time, these same communities — once scattered, vulnerable, and seeking refuge — became the very builders of modern Lebanon, whose foundations took formal shape with the creation of the Lebanese state in 1920.

Today, Lebanon endures extraordinary hardship, is infested with politics and rampant corruption, yet the spirit that sustained it for centuries remains unbroken. In a country of roughly 6.8 million, an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees and around 500,000 Palestinian refugees now reside within its borders — the highest number of refugees per capita anywhere in the world. The exact figures are imprecise and constantly shift, but the reality is unmistakable. Lebanon, while struggling under economic collapse, political paralysis, the scars of war, and the devastation of the 2020 Beirut port blast, carries a burden far larger than its size. And this crisis falls heavily on the Lebanese themselves, whose daily lives have been upended by a collapsing currency, failing institutions, and the slow erosion of a once-vibrant middle class. It is a crisis within a crisis — where a nation in distress should be responsible for those who seek safety within it, while its own people search for stability and dignity.

And yet, despite this immense strain, Lebanon continues to reveal the truth that has defined it across millennia: that it has always been more than just a place. That despite the mismanagement and corruption, it has been a refuge and a promise — a land where the displaced could find a relative measure of dignity, and where communities long at risk elsewhere were able to build lives, memories, and meaning – even in imperfect conditions. This legacy endures even now, in one of the most difficult chapters in Lebanon’s modern history.

And in this enduring role, Lebanon echoes a universal call, one captured in the words of American poet Emma Lazarus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”

And so, just like that modest chapel in the vast basilica, Lebanon continues to hold its role in a difficult region— not through brute power, but through a resilience capable of carrying far more than its proportions suggest.

Note: This essay focuses on only a selection of Lebanon’s historic communities. Many others — including Alawites, Ismailis, Armenians, Melkite Greek Catholics, Syriac Catholics and Orthodox, Chaldean Catholics, Assyrians, Protestants, and smaller Christian and Muslim denominations — have likewise contributed to the country’s cultural and spiritual life. Their stories are no less essential; they remain beyond the scope of this piece due solely to its length.

Ralph Hage is a Lebanese American architect and writer who spends his time between Lebanon and the United States. His work explores the intersections of art, architecture, and cultural heritage in Lebanon and across the Arab World.