The Medium of Arabic Instruction

By: Diksha Tyagi/Arab America Contributing Writer

The decision of what language to teach students and what language to teach in has become even more pertinent in an increasingly globalized world. Language represents culture, meaning, and identity. However, it has also become a tool of mobility and power. Similar to other nations around the globe, Arab countries must choose between emphasizing the use of Arabic and teaching its people a language that, though useful in global contexts, may weaken the role of local dialects and of Arabic as a whole. Languages and language policy in education across the Arab world have numerous complex impacts today.

Language in the Arab World

When we refer to Arabic, we aren’t referring to one monolithic language. Spoken dialects of Arabic vary immensely across the Arab world, across and even within borders. Many dialects can be understood by speakers of other dialects, but some have greater differences.

Written Arabic has been formalized through the use of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) starting in the late 19th century. This was done in order to bridge gaps between spoken dialects and to enable communication in formal settings. Now, MSA is taught in schools across the region and used in official contexts, but native speakers continue to rely on local dialects in daily life.

Across the region, foreign languages are also commonly taught, but the language and its use vary. English is taught as a second language in most regions due to its role as the dominant global lingua franca. Nations with a history of French colonization often retain French as the most widely used language after Arabic, but the popularity of English even in those countries is rapidly increasing. These all make the Arab world a highly multilingual area where governments must continually reassess linguistic policy.

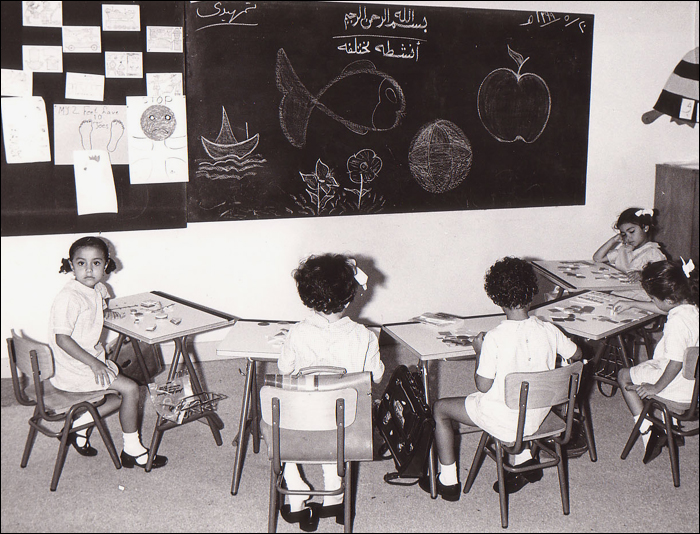

Arabic in Education

Many Arabic-speaking countries have formalized the use of Arabic by designating it as the official language of the state. This status often extends to education, where Arabic is the primary language of instruction in public schools. This is done with the intent of protecting and promoting the language, understanding its importance for cultural identity. However, certain subjects, higher education, and private schools have increasingly been switching to English or French.

For instance, in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, Arabic is the official language of instruction by law. The Saudi Basic Law of Governance identifies Arabic as the language of instruction, with English allowed only when “necessary”. The 2020 UAE Arabic Declaration emphasized and launched initiatives to protect and continue teaching the language. However, this doesn’t take away from the expanding use of English in everyday life. English is often used on social networking sites and by immigrant residents, therefore seeping into daily use. At the university level, STEM disciplines are usually taught in English. This is often justified as a practical response to globalization, especially for fields that depend on international collaboration.

In Algeria and Morocco, where the second most widely used language is French, Arabic is also legally mandated in public schools. Algeria’s policy of Arabization following independence succeeded in expanding Arabic-medium education over French in early education. However, French still remains the language of administration and higher education. In recent years, English has gained a greater foothold in university programs across the region as well, reflecting this emphasis on English as a key language of professional and scientific communication.

Practical Consequences

Policies intended to preserve Arabic can often produce unequal consequences. Laws requiring public schools to teach primarily in Arabic make it so that all citizens continue to formally learn the language. However, private schools, often less regulated, therefore end up more likely to teach English or French to students, sometimes as a second language and more often as the primary medium of instruction. These institutions frequently present foreign-language instruction as a tool for higher professional success. As a result, students from wealthier backgrounds are more likely to graduate with knowledge of a second language. Meanwhile, those educated in Arabic-medium schools may face disadvantages in the global labor market.

Yet, overemphasizing learning English or another second language over Arabic can also lead to negative consequences for the language. Surveys report growing use of English amongst youth, with 68 percent of youth in the Gulf in 2017 using English on a daily basis. Arabic literacy amongst youth in the UAE, the Arab nation with the highest English proficiency, has decreased even with a bilingual curriculum. Altogether, Arab countries must recognize the vast consequences of linguistic policy, which will have repercussions on the global scale. It isn’t a question of whether foreign languages should be taught, but how they can be without diminishing Arabic’s role and continuity throughout the region.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!