Pathbreakers of Arab America—Philip Hitti

By: John Mason / Arab America Contributing Writer

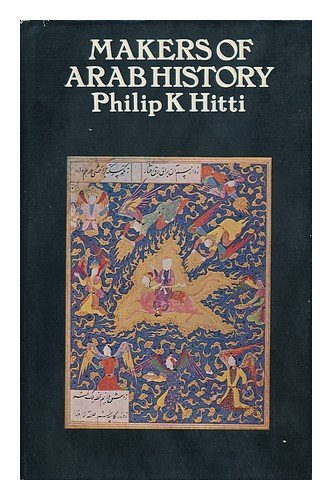

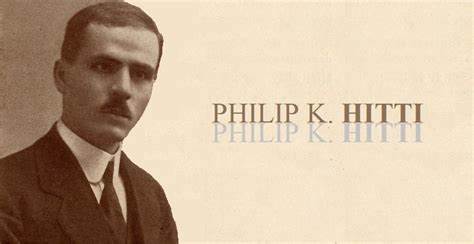

This is the eighty-first in Arab America’s series on American pathbreakers of Arab descent. The series features personalities from various fields, including entertainment, business, sports, science, the arts, academia, journalism, and politics, among others. Our eighty-first pathbreaker, Philip Hitti, is a Lebanese-born professor and scholar of Arab and Middle Eastern history, Islam, and Semitic languages, and a founder of Arab and Oriental studies in the U.S. Now deceased, Hitti was a strong proponent of an equitable political solution for Arabs who lived for centuries in what was historically known as Palestine.

Hitti almost single-handedly introduced generations of American students to Arab and Middle Eastern history, Islam, and Semitic languages

Phillip Khuri Hitti was born in the Lebanese governorate of Mount Lebanon on 22 June 1886. His parents were Maronite Christians who lived in the village of Shemlan, located 15 miles or so southeast of Beirut. According to the Wikipedia series on Arab Americans, Hitti was educated at an American Presbyterian mission school at Suq al-Gharb and then at the Syrian Protestant College. Upon graduating in 1908, he taught at the same school before moving to Columbia University, where he earned his PhD in 1915 and taught Semitic languages.

Following World War I, Philip returned to Lebanon, teaching there until 1926. His academic progress was rapid, for in the same year, Princeton University offered Hitti a Professorship of Semitic Literature and the chairmanship of the Department of Oriental Languages. He held those positions until his retirement in 1954. During World War II, he taught Arabic to servicemen at Princeton through the Army Specialized Training Program. Upon retirement, Hitti accepted a professorship in Middle Eastern studies at Harvard University. Hitti’s final full-time work included a research position at the University of Minnesota. He died in Princeton, New Jersey, on 24 December 1978. Hitti’s vast collection of research papers is housed at the University of Minnesota.

Hitti tells a story of how, as a Lebanese immigrant, he helped pave the way for Islam and Muslim culture studies in the U.S. This modest story is based on his unpublished memoir, stored in the archives in Minnesota. The story starts when he was eight years old, and he and his brother were taking the family donkey to pick up a sack of flour from a nearby village. Their father had told them to walk the donkey and never ride it. Boys being boys, and out of sight of their father, they hopped on the donkey, only shortly after to be thrown off. His brother was fine; however, for Hitti, the fall resulted in a compound fracture, projecting through the skin of his right arm.

Following the family’s attempt to nurse their patient, it became clear that Philip’s injury required professional care. Shortcutting the story a bit, along came a graduate of the school of medicine at the Syrian Protestant College — known today as the American University of Beirut — who was traveling through Shemlan and heard that a local boy required medical attention. “His prognosis: Hitti’s arm had developed gangrene. He had to choose between death or the hospital.” After this incident, the family decided that such a boy as their Philip “cannot make his living here; send him away to school.” Thus, after excelling at his local school, he ended up at the Syrian Protestant College–just like the student who sent him to the hospital.

Hitti became one of the first university professors to organize and teach courses on different peoples, their cultures, religions, and languages. Other universities subsequently adopted his initiative and began offering ethnic studies courses that better reflected America’s changing demographics. His initiative became part of a movement, which at the height of the fight for civil rights in the 1960s, argued for universities to introduce more courses on “non-European histories and cultures, create better opportunities and services for students of color, and increase hiring of non-white faculty.”

Hitti’s academic contributions were made at the beginning of the struggle in the 1960s to make the education system in the United States more inclusive along lines of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality. And thus, according to a source found in a publication named ‘The World,’ “One man — an immigrant who first came to the United States from Lebanon in 1913 — helped pave the way for greater diversity in American academics by pioneering the study of Islam in the United States. And it was all thanks to a broken arm.”

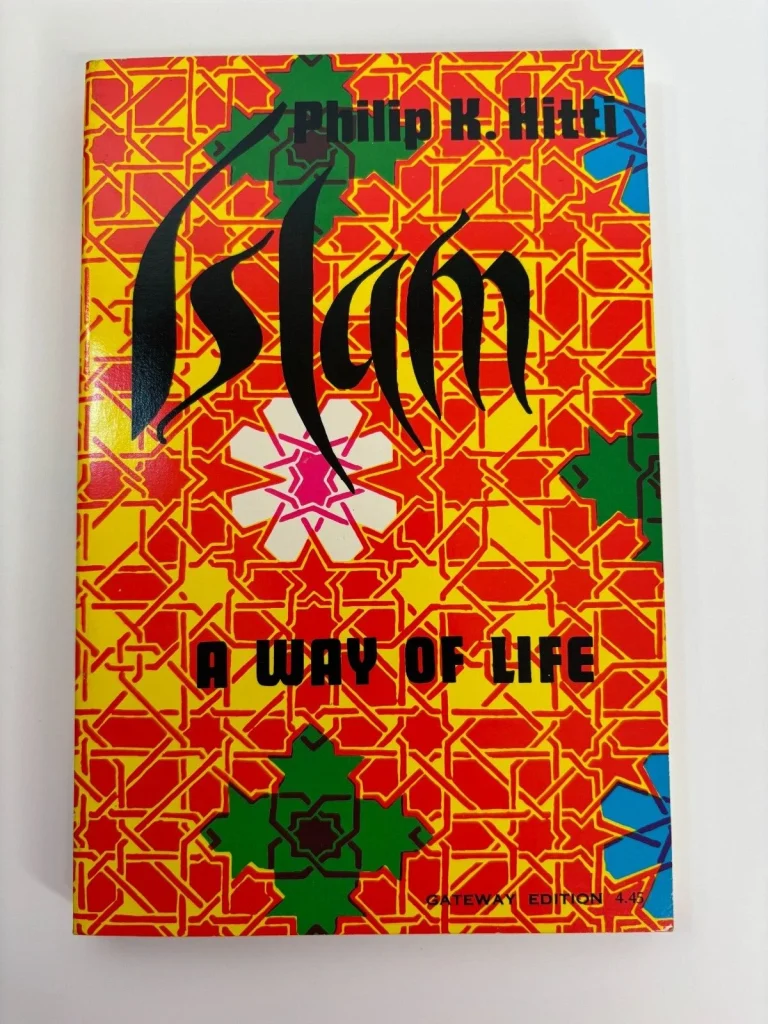

Hitti returned to Lebanon in 1920 as a professor of Oriental history at the renamed American University of Beirut, while in February 1926, he returned to the U.S. as an assistant professor of Semitic literature at Princeton. He was “perturbed by the university’s lack of coursework on Islam — the curriculum only offered classes that taught Islam as it related to Christianity and Judaism.” As for language, Hitti explained there were no classes at Princeton or anywhere else in the U.S. that focused on “Arabic for its own sake, as a carrier of a major world culture and as a key to one of the richest literatures.”

Hitti’s response was to create graduate courses in Arabic, Turkish, and Persian languages, and to recruit and teach courses on the literature, history, religion, economics, sociology, politics, and arts of the Near East. When he tried to convince university administrators about “the merits of Islamic Studies,” Hitti remembered feeling like “Americans had inherited from Europeans a measure of political and religious prejudice against Islam.” It took 20 years, but in the mid-1940s, Hitti founded and became the first director of Princeton University’s Program in Near Eastern Studies.

Hitti’s solid support for Palestinian Arabs rattled some American political Zionists

Hitti was vocal in his support of Palestinian Arabs, testifying as early as 1944 before a U. S. House committee. His testimony gave support to the view that “there was no historical justification for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.” In 1945, Hitti served as an adviser to the Iraqi delegation at the San Francisco Conference, which established the United Nations. In 1946, Hitti was the first Lebanese-American witness at the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine. He explained that “there was actually no such entity as Palestine – never had been; it was historically part of Syria…”

According to the Journal of Arab Studies Quarterly, Hitti “traced the history of Palestine back 7000 years. All that time, he said, it had been the immemorial home of the Arabs. He asserted that Zionism was indefensible and unfeasible on moral, historic, and practical grounds. It was an imposition on the Arabs of an alien way of life which they resented and to which they would never submit.” Hitti devoted considerable time outside of Princeton classrooms to enhance American understanding of Arabs and to promoting the Arabs’ case on Palestine.

In balancing his testimony before Congress, Hitti voiced sympathy for European Jews but pointedly blamed the Nazi regime for creating “the Jewish problem,” which Palestinian Arabs and Muslims should not have to fix. He further noted, “Nothing, in the judgment of the speaker, is more conducive to a state of perpetual unrest and conflict than the establishment of a Jewish commonwealth at the expense of the Arabs in Palestine.” Hitti was even critical of the U.S., which refused to change its policy that would have admitted millions of Jewish refugees to settle here.

Hitti was prescient in stating his views as early as March 1945 on a potential Israeli state in the place of Palestine. Titled “The Arab Claim to Palestine,” he conjectured that “A Zionist state is both impracticable and indefensible—a perpetual source of unrest and disturbance in the Near East.” He characterized political Zionism as “the rankest kind of imperialism” and “an attenuated form of conquest,” adding, somewhat hyperbolically, that “Arabs in the Near East saw every Zionist coming in as a potential warrior.”

A seeming sideshow emanated at Princeton from Hitti’s advocacy and testimony on the Palestine issue, a personal conflict between him and the celebrated Albert Einstein, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, who worked at the Institute for Advanced Study, then located in a building on Princeton’s campus. Hitti had stated, “Einstein was a Zionist, though his support for Jewish settlement in Palestine, or cultural Zionism, did not extend to the establishment of a Jewish state, or political Zionism.” In any case, it was unclear that Hitti and Einstein were ever close personally.

As to Hitti’s commentary on the Palestine issue, “He always insisted that Palestine belonged to the Arabs, its occupiers for centuries. True, he failed to convince American decision-makers, but the point is that his thoughts on the Palestine issue were clear, crisp,

and consistent.”

The politics surrounding the Palestine issue aside, we conclude that Hitti inestimably contributed to the strong intellectual and scholarly tradition of interpreting the region of the Middle East to a broad audience. His contribution to understanding Arabs and other peoples of the Middle East, including their histories, societies, cultures, religions, languages, and politics, is inestimable.

Sources:

–“Phillip Hitti,” Wikipedia Series on Arab Americans, 2025

–“How a Lebanese immigrant helped pave the way for the study of Islam and Muslim culture in the US,” The World, 12/5/2016

–“Revisiting Hitti’s Thoughts on Palestine and Arab Identity,” Gregory J. Shibley, Journal of Arab Studies Quarterly, 4/1/2019

John Mason, Ph.D., focuses on Arab culture, society, and history and is the author of LEFT-HANDED IN AN ISLAMIC WORLD: An Anthropologist’s Journey into the Middle East, New Academia Publishing, 2017. He has taught at the University of Libya, Benghazi, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and the American University in Cairo; John served with the United Nations in Tripoli, Libya, and consulted extensively on socioeconomic and political development for USAID and the World Bank in 65 countries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab America. The reproduction of this article is permissible with proper credit to Arab America and the author.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!