What If the Best Reggae You've Never Heard Came From Libya?

By: Nourelhoda Alashlem / Arab America Contributing Writer

When people think of Libya, they rarely think of music. This is largely because, for decades, artistic expression faced heavy control. During the Gaddafi era, music that did not serve the state narrative was censored or pushed out of public space. Independent musicians often worked in secret. They recorded in small studios or at home and shared songs privately because official platforms were closed.

Yet music persisted.

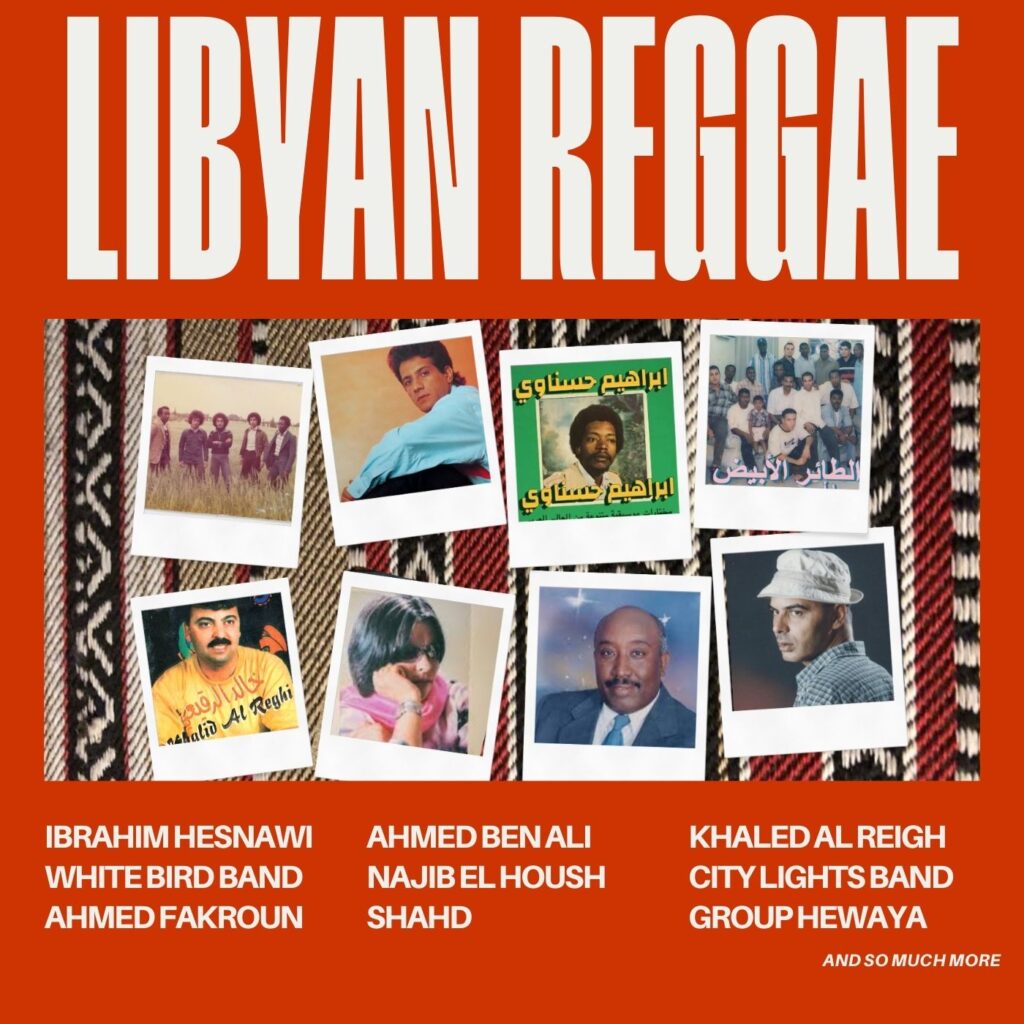

For many Libyans, including my own family, reggae became one of the few genres that felt allowed for the authentic Libyan identity to be free. The sounds of my childhood were White Bird Band, Najib El Housh, Ahmed Fakroun, and Ahmed Ben Ali on cassette tapes. Their music traveled from house to house, car to car, relative to relative. At a time when expressionism was considered dangerous, reggae emerged as a language of revolutionary resistance through rhythm.

So when global outlets describe Libya as a country “without music,” something feels deeply wrong. Libya always had music. It had innovation, creativity, and sound archives that lived outside official systems. One of the most fascinating chapters in that history is Libyan reggae. It grew from the heartbeat of Libyan folklore fused with Jamaican rhythm.

Today, this music finally resurfaces for the world. Much of that rediscovery comes through Habibi Funk Records. Their archival work has brought buried Libyan artists back into conversation and onto the global map. Their releases prove what many Libyans have always known: our country did not lack music. It lacked recognition. This article seeks to correct the record. Libya has music. Libya has a cultural history. And Libyan reggae is one of its most compelling stories.

How Did Reggae Reach Libya?

Reggae arrived in Libya in the 1970s through imported tapes and records. Libyans listened to Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, The Wailers, and later Lucky Dube. These sounds felt familiar. As Ahmed Ben Ali explains:

“The Libyan folkloric rhythm is very similar to reggae. When Libyans hear reggae, it feels natural.”

Rather than imitate Jamaican sound, Libyan musicians began to experiment. They incorporated:

- Traditional Libyan melodic structures

- Arabic lyrics and poetry

- Percussion such as the darbuka (دربوكة)

- Instruments like the oud (عود), and zukra (زكرة)),

- The classic reggae backbone of electric guitar, bass, and drums

The result preserved reggae’s off-beat rhythm, but the sound changed. It became distinctly Libyan. Musicians layered local melodies, Arabic phrasing, and regional percussion into the structure of reggae, creating songs that reflected everyday life in Libya. Themes often centered on social pressure, belonging, migration, economic struggle, and dignity. The music did not romanticize hardship, but it refused to give up on the future.

By the 1980s and 1990s, Libyan reggae had developed into a recognizable style inside the country. Much of it circulated only through home recording networks and cassette markets, which meant it rarely crossed national borders.

The Musicians Who Defined Libyan Reggae

We cannot talk about Libyan reggae without talking about the people who built it. These musicians carved space for creativity when almost none existed.

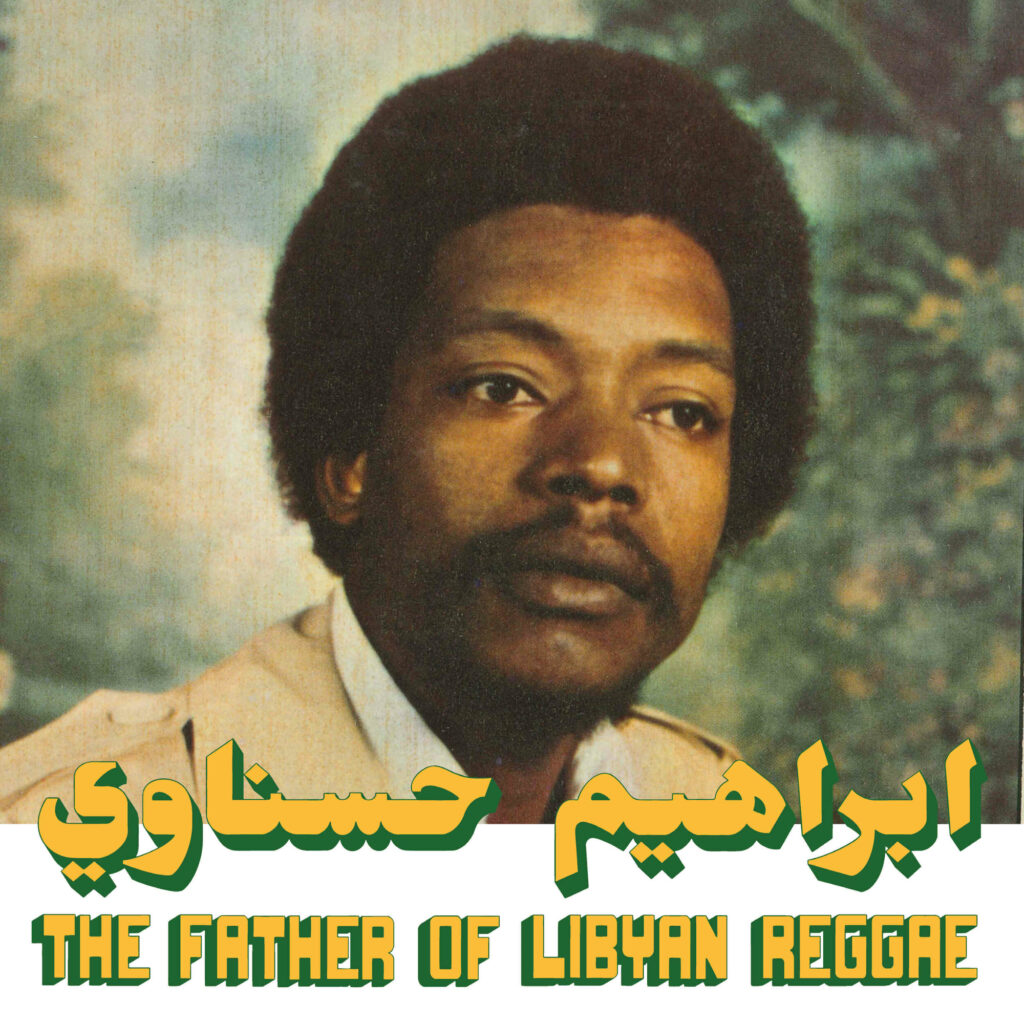

Ibrahim Hesnawi

Ibrahim Hesnawi, who is frequently referred to as the “Father of Libyan reggae,” was born and raised in Tripoli at a time when there were few opportunities for experimentation in Libyan music. Hesnawi, who was greatly influenced by Bob Marley, approached reggae as something that already resonated with Libyan folkloric rhythm and vocal repetition rather than as an imitation. He was employed during the day as a customs officer at the Tripoli port. He recorded and music at night that would subtly spread reggae throughout the nation. His songs became popular in private parties, taxis, and cassettes, setting the stage for a whole generation of Libyan reggae musicians. Through the efforts of Habibi Funk Records, which is creating full-length releases devoted to Hesnawi, his work has been preserved and reintroduced decades later, guaranteeing that his legacy stays a part of Libya’s musical record.

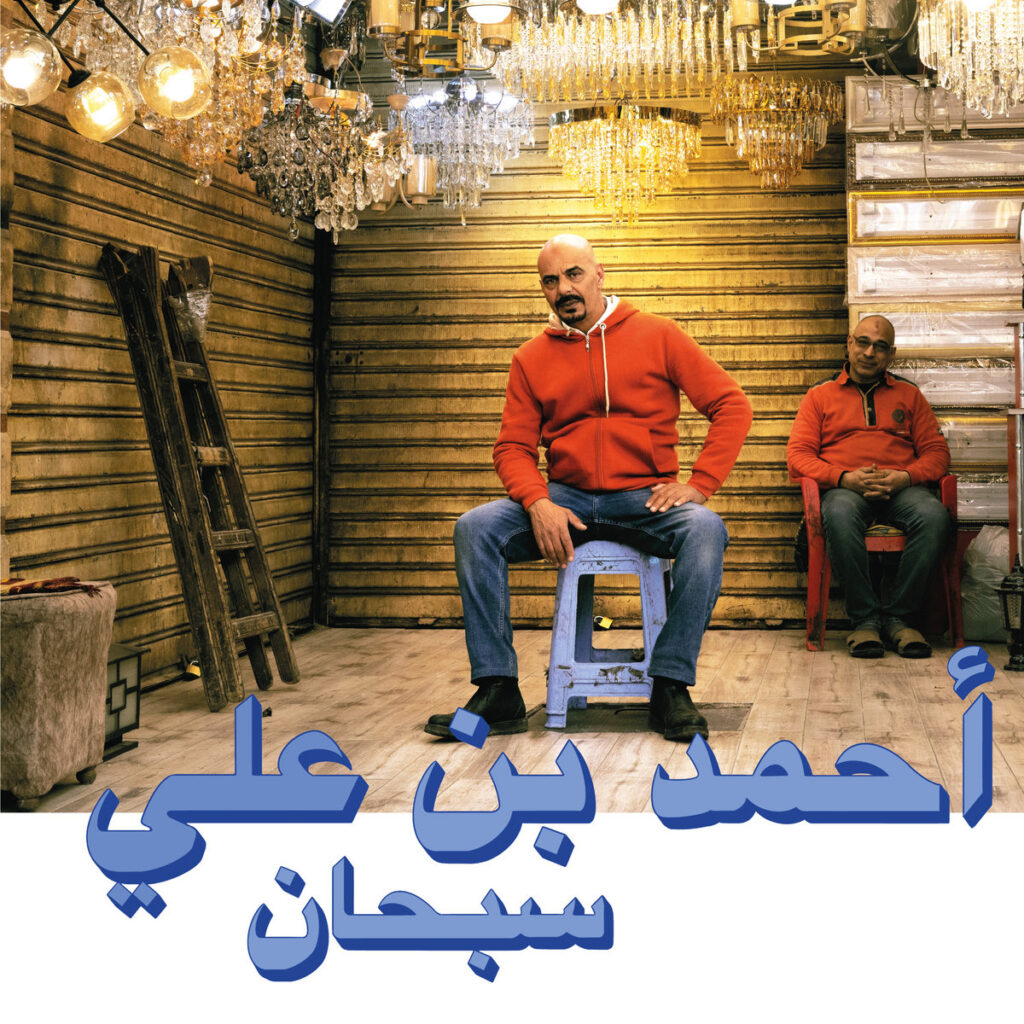

Ahmed Ben Ali

Ahmed Ben Ali is a Benghazi technical engineer. He recorded a large portion of his music at home in the early 2000s, outside of any official industry framework. After being recorded in 2008, his song “Subhana” went unnoticed for a while before unexpectedly becoming well-known online years later. It eventually received over a million plays on YouTube and reappeared on TikTok.

Ben Ali himself remained relatively unknown despite this prominence, illustrating how disconnected Libyan musicians were from international recognition. Ben Ali stressed that Libyan reggae is unique rather than diluted when considering his sound. He noted that Libyan folkloric rhythm already closely resembles the structure of reggae, which explains why Libyan listeners found the genre familiar and approachable. According to his interview with Test Pressing, Ben Ali states, Libyan reggae is “original reggae—Libyan style,” which is based on regional musical reasoning as opposed to outside imitation.

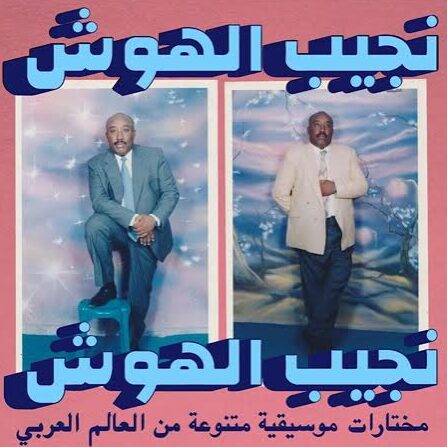

Najib Alhoush and The Free Music Band

Born in the southern Libyan city of Wazin, Najib Alhoush began his musical career in 1972 and quickly became a central figure in Libya’s evolving soundscape. Alongside saxophonist Salem Gebril and guitarist Mohamed el Sayed, he formed Free Music Band (Almoseeqa Alhora), a group that merged reggae, funk, disco, and rock with Libyan Arabic poetry and lyrics. Their time spent in Italy exposed them to new sonic possibilities, which they folded back into Libyan musical traditions. Over the course of six albums, the band reshaped Libyan popular music before political pressure, economic decline, and the collapse of the music industry in the mid-1980s curtailed their work. Alhoush later continued as a solo artist through the 1990s and 2000s, releasing songs that remain foundational to Libya’s modern musical memory.

Ahmed Fakroun

Ahmed Fakroun, born in Benghazi, represents another dimension of Libyan reggae’s evolution.While not exclusively a reggae artist, Fakroun incorporated reggae rhythms and sensibilities into his work during the 1970s and 1980s, helping normalize the genre within Libyan popular music. His experimentation showed that reggae could coexist with Libyan melody and Arabic lyrics, contributing to its acceptance beyond underground circles.

Fakroun’s use of reggae elements appeared alongside traditional instruments such as the oud and darbuka, combined with electric guitar, bass, and keyboards. This fusion reinforced the idea that reggae aligned naturally with Libyan folkloric rhythm rather than standing in opposition to it. At a time when political pressure limited artistic freedom, Fakroun’s music helped expand the sonic vocabulary available to Libyan musicians, indirectly influencing later reggae-focused artists by demonstrating that global rhythms could be adapted into a distinctly Libyan sound.

Shahd

One of the few prominent female voices in Libyan reggae-influenced music, Shahd emerged in the early 2000s after a chance encounter with Ibrahim Hesnawi, who recognized her talent and encouraged her to explore reggae more deeply. Her debut album achieved significant success, yet she remained intentionally anonymous, navigating a conservative society. Shahd later recalled walking into music stores, riding in taxis, and hearing her own songs played without anyone realizing she was the singer. Her story illustrates both the influence of Libyan reggae and the social constraints that shaped its development, particularly for female artists.

The White Birds Band

Often known as the most influential reggae band in Libya, White Birds Band played a central role in establishing reggae as a lasting musical force in the country. Founded in 1984, the group formed out of close friendship and a shared belief in music as a vehicle for peace, justice, and unity. Their name symbolized those values, with the “white bird” representing peace and hope.

The band formally began releasing music in the early 1990s, issuing their first album in 1993. Reggae stood at the core of their sound, not only musically but philosophically. The band connected reggae’s message of resistance and dignity to Libyan social realities, which helped the genre resonate widely

Despite limited access to studios and international platforms, White Birds collaborated with artists inside and outside Libya, including musicians from across Africa. Political conditions kept their work largely undocumented beyond Libya, but their influence remained strong locally. Today, the digitization of their cassette recordings marks a long-overdue recognition of a band that helped shape Libyan reggae from its earliest years.

Watch a short interview film with the White Birds Band here.

Khaled Al Reigh

Khaled Al Reigh held a unique position in Libya’s musical landscape. He was well-known for his contributions to children’s television programming, but he also had a significant impact on Libyan band culture beginning in the 1970s. Al Reigh, through groups like Nujoom Al-Andalus and Angham Al Horreya, influenced a generation of Libyan music that combined education, social messaging, and experimentation. His later solo work, which includes the song “Zannik,” exemplifies how Libyan artists constantly cross genres while responding to global influences, even under restrictive conditions.

Libyan Reggae to the World

Libyan reggae challenges the idea that Libya exists outside cultural production. It tells a story of creativity under constraint, of global sound translated into local expression, and of music that survived without institutions or recognition. For decades, these songs lived quietly in homes, cars, and cassette collections, carried by families who never stopped listening.

This article cannot name every Libyan reggae artist. There are far too many to do so. That fact alone speaks to the richness of Libya’s musical culture and the depth of what has long gone unheard.

On behalf of Libyans, we extend sincere gratitude to Habibi Funk Records for honoring this music with care, integrity, and intention. Their archival work did not create Libyan music. It recognized it. It returned voices to history that were never meant to disappear, only to be heard and understood on their own terms.

Libya has music.

Libya always had music.

And finally, the world is beginning to listen.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!