What Is Yennayer? Inside the Amazigh New Year Celebrated Across North Africa

By: Nourelhoda Alashlem / Arab America Contributing Writer

Today, January 12, 2026, Amazigh communities across North Africa are celebrating Yennayer 2976. This marks the Amazigh New Year, one of the oldest New Year celebrations in the world! People celebrate the holiday for three days each year, from January 12 to 14. Yennayer is the start of the agrarian year. Amazigh people have long understood time through land, rain, and the changing seasons. Long before modern calendars or borders, they measured the year by harvests and weather rather than fixed dates.

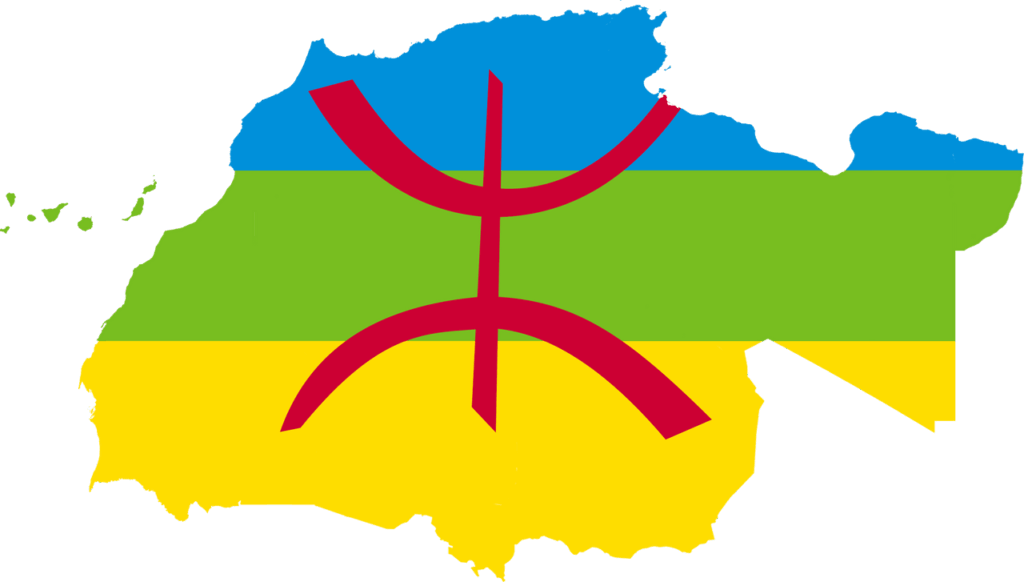

The Amazigh, who are also known as the Imazighen, meaning “free people,” are the Indigenous people of North Africa. Their presence stretches across Libya, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt’s Siwa Oasis, and the Sahara. This region is often referred to as Tamazgha. While Amazigh communities later adopted Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, their languages, traditions, and agrarian customs continued to exist.

To this day, Yennayer continues to be more than a celebration; it’s one of the many ways the Amazigh people preserve and pass on their culture, identity, and heritage across generations.

Tracing the Origins of the Amazigh Calendar

Yennayer is the first month of the Amazigh calendar. The first day of Yennayer corresponds to the first day of January in the Julian calendar, which is thirteen days compared to the Gregorian calendar. This places Yennayer on January 12 each year. Despite the Amazigh calendar being formally systematized in 1980 by Algerian scholar Ammar Negadi, its starting point was intentionally set much earlier.

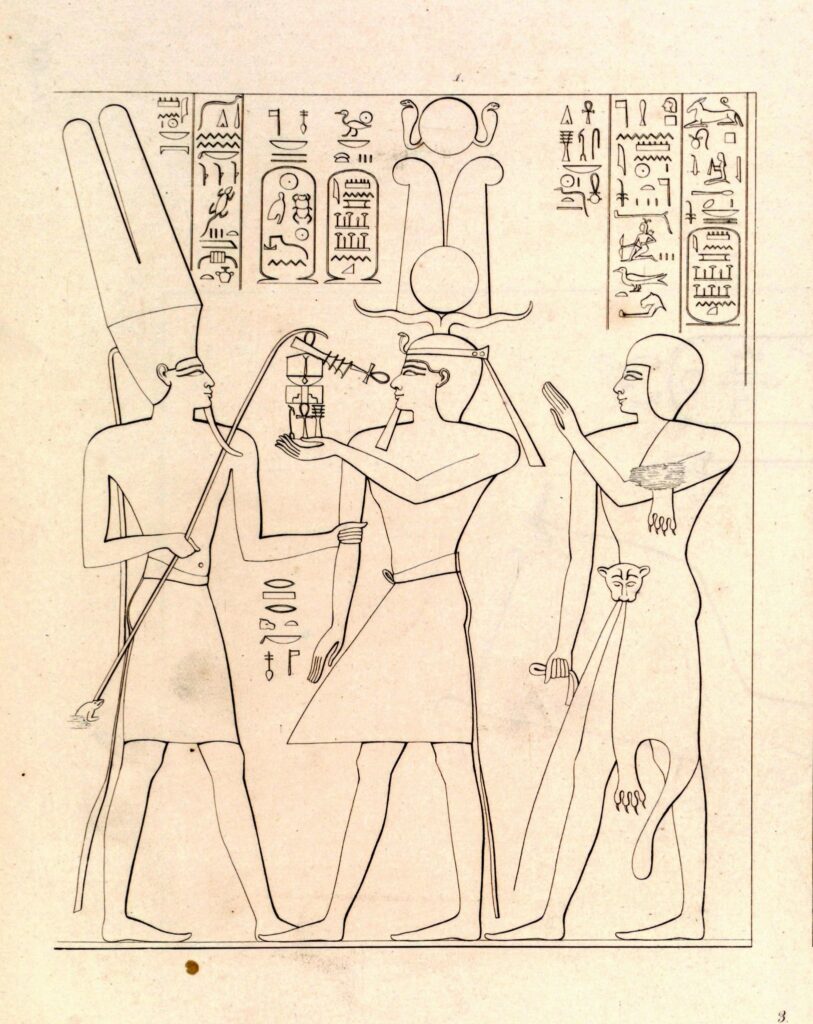

The Amazigh calendar traditionally begins in 950 BCE, a date linked with the rise of King Sheshonq I, a Libyan ruler from the Meshwesh, an ancient Amazigh tribe, who were in almost constant conflict with the Egyptian state and later settled there. Sheshonq later became Pharaoh of Egypt and founded the Twenty-Second Dynasty. This marked a moment when Amazigh leadership reached the highest level of political power in the region.

The year 950 BCE ultimately represents continuity, sovereignty, and historical depth. Today, the Amazigh calendar functions less as a literal historical record and more as a cultural affirmation that Amazigh history stretches back thousands of years.

Yennayer in Libya

In Libya’s Amazigh regions, particularly the Jabal Nafusa mountains, Yennayer is closely tied to rainfall and agricultural fortune. Many Amazigh communities see rain on Yennayer as a sign of blessing and a prosperous year ahead. This year, people across Jabal celebrated the rainfall as a hopeful sign after years of environmental and economic strain.

Food plays a central role in Libyan Amazigh communities. Many prepare tamoqtal (تموقتال), a traditional dish made from wheat seeds cooked in a dark red sauce with peas and lentils, often slow-simmered with dried sheep’s head meat. Alongside it, families also prepare Ellousa (اللوسة), a food passed down from generations. Ellousa is prepared by drying onions, tomatoes, peppers, and garlic, then cooking and blending them with olive oil. Its preparation reflects a deep connection to the land, relying on sun-drying and seasonal ingredients from the mountains.

Another widespread tradition involves preparing couscous, often with seven vegetables, as the number is associated with unity. In many households, elders hide a date inside a large communal bowl known as a gasʿa (see image on left), and children search for it as they eat. Families believe the child who finds it carries good luck for the year.

Sweets and dried figs symbolize baraka—divine grace and blessing—and circulate through the community, reaching relatives, neighbors, and those in need.

Historically, communities also gathered for collective rain-invoking dances set to traditional music, a practice that has unfortunately largely faded over time.

Yennayer in Algeria

Algeria is home to some of the most widely practiced public Yennayer celebrations, particularly in Kabylia, the Aurès Mountains, and among Chaoui, Mozabite, and Tuareg communities.

Food is also central to the Yennayer in Algeria. Just like in Libya, Algerian Amazigh families similarly prepare couscous with seven vegetables or seven grains. Other traditional dishes include berkoukes, a hearty grain-based stew, and tamina, a sweet made from toasted semolina mixed with butter and honey.

Another popular Yennayer tradition is Treiz, a custom found throughout North Africa. Families prepare a blend of nuts, dried fruits, and sweets and pour it over the youngest child to symbolize prosperity. In some regions, elders seat children on a wooden board and toss nuts and grains around them to bless the new year with fertility and protection.

Beyond household festivities, Yennayer comes alive through public festivals and street celebrations. One of the most famous is the Ayrad (Lion) Carnival in Tlemcen/Béni Snous (see article on right). The semi-theatrical carnival features masked performances, symbolic animal figures, storytelling, and the distribution of dried fruits and agricultural goods. This is all meant to welcome the new year with joy and hope for a fertile agricultural season.

In 2018, Algeria became the first country in North Africa to officially recognize Yennayer as a national public holiday. This marked a major step in acknowledging Amazigh culture at the state level. Today, families and communities across the country celebrate the holiday together, in a celebration rooted in history and identity.

Yennayer in Morocco

In Morocco, Yennayer is celebrated across the Atlas Mountains, Souss, Rif, and other Amazigh regions. In terms of food, families commonly prepare tagoula, a thick porridge made from barley or cornmeal and topped with butter, honey, or argan oil. Like its neighbors, Moroccan families prepare couscous with seven vegetables to honor the earth’s bounty at the start of the agricultural year.

The celebration also revolves around music and social gatherings. This consists of collective dances like ahwach and ahidous that unite entire communities. To welcome renewal and purge the past, bonfires are lit in some areas to commemorate the start of the new year.

In May 2023, Morocco officially declared Yennayer a paid national holiday, a decision that followed decades of advocacy by Amazigh activists. People widely welcomed the move as a step toward preserving cultural diversity and strengthening Amazigh identity. It also builds on earlier milestones, including the King’s 2001 speech in Ajdir. This marked a turning point in state recognition of Amazigh culture and language, as well as reforms that affirmed Amazigh as a core component of Morocco’s national identity.

Yennayer in Tunisia

In Tunisia, Yennayer is celebrated from the caves of Matmata to Amazigh villages in Tataouine, Gafsa, Djerba, and Sejnane. In many households, families dye and share eggs to symbolize renewal, fertility, and new life for the year ahead. Similar to other North African regions, Amazigh Tunisian families celebrate Yennayer by preparing couscous with seven vegetables or grains, expressing gratitude for the land, and marking the start of the agricultural year.

In Tamezret, a small Amazigh village in southern Tunisia, Yennayer is marked by annual community celebrations featuring traditional Malouf music, folk songs, and traditional Amazigh clothing, bringing families and visitors together in a shared expression of heritage and continuity.

Unlike neighboring countries, Tunisia does not officially recognize Yennayer as a national holiday. The Amazigh identity remains largely absent from state narratives. Although Amazigh associations estimate that over one million Tunisians have Amazigh roots, decades of forced Arabization, similar to Libya, have contributed to the decline of the Tamazight language. However, many Tunisians continue to identify culturally as Amazigh.

Even when celebrated discreetly, Yennayer in Tunisia remains a powerful expression of resilience and belonging.

Yennayer in Egypt (Siwa Oasis)

In Siwa Oasis, Yennayer carries layers of history that stretch far beyond the modern Egyptian state. The oasis itself takes its name from the indigenous Ti-Swa tribe. Archaeological and historical research traces Siwa’s prehistoric inhabitants to North Africa, particularly Libya, where they shared cultural and social patterns with Amazigh communities across the Maghreb.

Yennayer in Siwa today is marked with families gathering to share traditional foods such as dates, olives, bread, and Egyptian sweet couscous. Traditions also include home cleansing with bakoor, new clothes are worn, and elders offer blessings for prosperity, health, and rainfall in the coming year. While celebrations are largely private, they still highlight Siwa’s deep connection to the Amazigh calendar and the land itself.

In a country where Amazigh identity remains largely unrecognized at the state level, Yennayer in Siwa is more than a New Year celebration. It is an act of cultural continuity, a reminder that the Amazigh presence in Egypt predates modern borders, empires, and political narratives and remains rooted in the oasis of the desert.

Why Yennayer Still Matters

Today, Amazigh communities across North Africa and the diaspora welcome Yennayer 2976. As North Africa moves forward, Yennayer remains a living testament to the endurance of Amazigh culture across the region. Today, each year, on January 12, when people gather to say “Aseggas Amaynou” and share couscous with seven vegetables, they take part in a celebration rooted in the earliest agricultural life of these lands.

Yennayer holds particular importance given the long history of marginalization and erasure faced by the Amazigh identity. Yet, history tells a different story. North Africa remains Amazigh at its core, whether that demographically, culturally, linguistically, and historically, even where Arabic is spoken.

The greeting “Aseggas Ameggaz” means Happy New Year in Tamazight, but it also carries a deeper wish—for renewal, abundance, and life rooted in the land.

Aseggas Ameggaz!

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!