Youssef Aftimus-A Pioneer of Architectural Revival and Urban Vision in Lebanon

By Ralph I. Hage/Arab America Contributing Writer

Youssef Aftimus, born on 25 November 1866 in Deir el Qamar, within the Chouf region of what was then the Ottoman Empire, emerged as a major civil engineer and architect whose style melded Moorish Revival aesthetics with urban planning in early 20th-century Beirut.

Early Life and Education

Aftimus was raised in a Greek Catholic family in the historic town of Deir el Qamar. His education began at the Collège des Frères Maristes around 1875. By 1879, he had progressed to the Syrian Protestant College, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree. Prior to his journey abroad, he taught Arabic at the same institution for two years and even co-authored an Arabic grammar textbook – a testament to his early literary and academic inclinations.

In 1885, Aftimus traveled to New York City to study civil engineering at Union College, graduating in 1891. His initial professional tenure was with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, working on the Hudson Canal project and Pennsylvania rail lines. Subsequent stints followed with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company and General Electric.

Rise as an Architect of Global Stature

Aftimus’s entrance onto the global architectural stage came in 1893, when he was chosen to design several pavilions – Persian Palace, Turkish Village, and Cairo Street – for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Particularly, the Cairo Street pavilion was a notable crowd-puller. This marked a significant foray into Moorish Revival architecture, framing his stylistic perspective and anchoring his later contributions in Beirut and the broader Levant.

His work extended beyond Chicago, including involvement with the Egyptian pavilion at the Antwerp International Exposition in 1894, followed by a research visit to Berlin in 1895 focused on construction engineering. He returned to Beirut in late 1896.

Architectural and Urban Legacy in Beirut

In 1898, Aftimus was appointed municipal engineer of Beirut. One of his early notable contributions was the design of the Hamidiyyeh Fountain in 1900, dedicated to Sultan Abdulhamid II. Originally located at Riad el-Solh/as‑Sour square, the fountain was later relocated to Sanayeh Park, where it still stands.

Aftimus founded a consulting office in 1911 alongside Emile Kacho, another engineer. The next decade saw some of his most enduring projects. In 1923, Aftimus won the design competition for Beirut’s City Hall (municipal building), situated at the prominent intersection of Weygand and Foch streets—a structure that endures as a civic landmark today.

His public service extended beyond architecture: he held the position of Minister of Public Works in the 1926–1927 government under Prime Minister Auguste Basha Adib.

Among his broader portfolio, Aftimus contributed to:

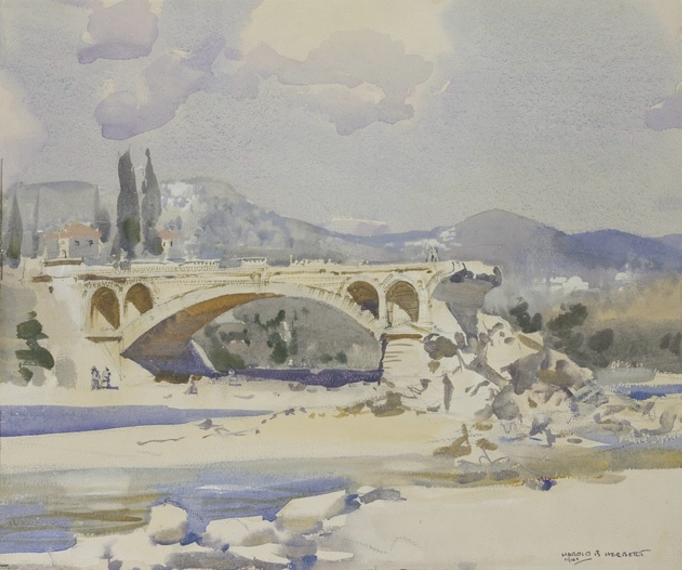

- The Old Damour bridge (1920), later damaged in 1941.

- Water infrastructure in Nabatiyeh (1924).

- Nicolas Barakat Building (1924), and buildings for the Hôtel-Dieu de France hospital (1925).

- His own Aftimus House in Kantari (1927).

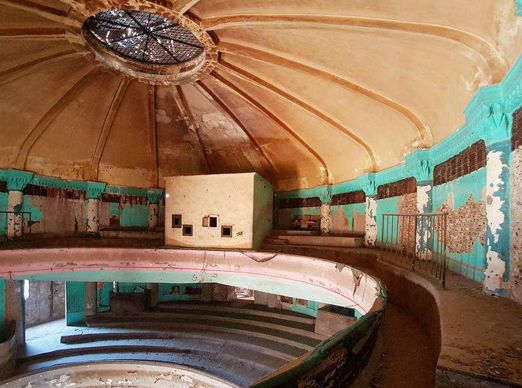

- Conference halls and residences like the Issa Building (also hosting the U.S. consulate) and the Le Grand Théâtre de Beirut (1929).

- The Mugar Building at Haïgazian University and works at Beirut University College (1932–33).

An ambitious – but unrealized – project in 1935 was his design for a Greek Catholic cathedral, which never came to fruition.

Aftimus’s influence extended beyond his built works. He co-authored a published treatise on Arab architecture, titled العرب في فن البناء, and was inducted into the Arab Academy based in Damascus. He also served as president for the Syrian Protestant College alumni association, showcasing his continued engagement with academic and institutional communities. Notably, he was a force in the fight against tuberculosis, founding and leading a non-profit charity to combat the disease.

Cultural and Architectural Impact

Aftimus emerged during an era marked by an Ottoman architectural revivalist movement, which sought to define a distinct Ottoman architectural identity. This movement was sparked by the 1873 publication of Usul‑i Mimari‑i Osmani (“Principles of Ottoman Architecture”) under commission by Ibrahim Edhem Pasha. It blended disparate styles like Ottoman Baroque, Beaux-Arts, Neoclassicism, and Islamic motifs.

Aftimus’s exposure to Western exhibitions, particularly at Chicago, along with his experience in Beirut, positioned him uniquely to import an Ottoman revivalist style from Istanbul and the Columbian Exposition into Beirut by the late 19th century. His designs dominated public building styles in Beirut during the final decades of Ottoman rule.

Beit Beirut

The Barakat Building, also known as the “Yellow House,” and now, “Beit Beirut,” was one of Aftimus’s iconic designs. Severely damaged during the Lebanese Civil War and located in Achrafieh’s Sodeco area, it was slated for demolition in 1997. However, concerted efforts led by Lebanese activists along with media campaigns and public rallies, preserved the building.

An artistic intervention by Atelier de Recherche ALBA in 2000, exploring the building and neighborhood narratives, amplified the conservation campaign. In 2003, demolition plans were halted, and Beirut Municipality acquired the property to create a city memory museum chronicling the city’s 7,000-year history. With support from the government of France, restoration efforts progressed and culminated in the inauguration of Beit Beirut in 2017.

A Lasting Legacy

Youssef Aftimus passed away on 10 September 1952, but his architectural and urban legacy endures. As a masterful synthesizer of Moorish and revivalist aesthetics with pragmatic urban design, he shaped the face of modern Beirut. His influence stretched from civic edifices like Beirut City Hall to cultural memory sites such as Beit Beirut. With roles encompassing engineering, politics, education, and philanthropy, Aftimus stands as a defining elder figure in Lebanese – and broader Middle Eastern – architectural history.

Ralph Hage is an architect and writer whose work explores the intersections of art, architecture, and cultural heritage in Lebanon and across the Arab world.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!