The Traditional Architecture of Iraq

By Ralph I. Hage/Arab America Contributing Writer

The traditional architecture of Iraq spans millennia, shaped by diverse civilizations and unique environmental needs. From the ancient ziggurats of Sumer to the brickwork of Abbasid mosques and the inward-facing homes of Mosul and Basra, Iraqi architecture reflects a continuous dialogue between heritage, function, and identity.

Mesopotamian Foundations: Ziggurats and Ancient Forms

Iraq’s architectural history begins in ancient Mesopotamia, often called the cradle of civilization. Perhaps the most iconic example is the Great Ziggurat of Ur, built around 2100 BCE under King Ur-Nammu. This massive temple, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, was made of sun-dried and baked mud bricks layered with bitumen.

Equally significant is the Taq Kasra (also known as the Arch of Ctesiphon), a remnant of the Persian Sassanian empire dating to the 3rd to 6th centuries CE. Located near modern-day Baghdad, it features the world’s largest unreinforced brick vault – an engineering marvel of its time.

These early examples emphasize essential features of Iraqi architecture. The reliance on brick as a durable local material, symmetry in design, and monumental religious and political symbolism.

Islamic Golden Age: Abbasid and Ottoman-Era Monuments

With the rise of Islam in the 7th century, Iraq became a cultural and political heartland under the Abbasid Caliphate. New architectural forms emerged, blending Persian, Roman, and Islamic elements.

A prime example is the Great Mosque of Samarra, built in 848 CE under Caliph Al-Mutawakkil. This mosque is one of the largest ever constructed in terms of area and features the famous Malwiya Minaret. This 52-meter spiraling tower was believed to have served as a call-to-prayer platform and a symbol of power. The adjacent Abu Dulaf Mosque, built in 859 CE, follows similar principles of vast open courtyards.

Both mosques showcase Abbasid architectural priorities. These priorities include: massive scale, simplicity in decoration, and adaptability to local materials.

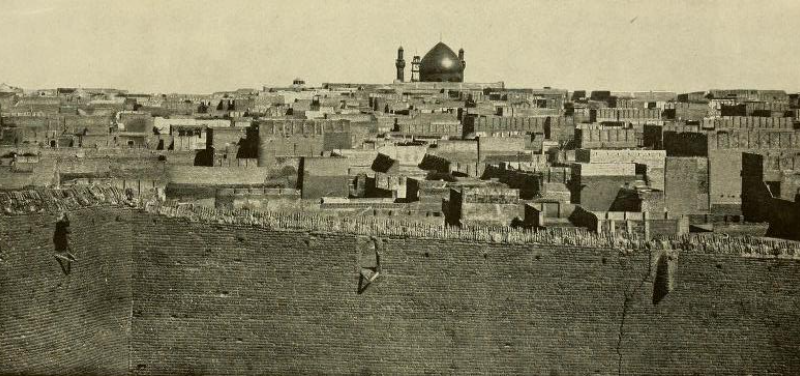

Baghdad and Later Abbasid Heritage

In the capital, the Qamariya Mosque, built in 1242 CE, stands as one of Baghdad’s oldest surviving Abbasid-era mosques. Its six domes, brick minaret, and interior tilework reflect a period of architectural refinement. The Great Mosque of Kufa, built in 670 CE and repeatedly restored, remains a pilgrimage site. Its large courtyard, arcades, and shrine enclosures show the early evolution of mosque planning.

Fortresses and Palatial Complexes

The Al-Ukhaidir Fortress, built around 775 CE, is a striking example of Abbasid-era fortified palace architecture. Situated south of Karbala, it contains a mosque, living quarters, storerooms, and courtyards – all enclosed in massive defensive walls. Its integration of defensive and residential functions is rare and uniquely Iraqi.

Vernacular Architecture: Courtyard Houses of Mosul, Najaf, and Basra

Beyond monumental architecture, Iraq’s cities are rich in vernacular traditions. Especially courtyard-based homes that adapt to social customs and harsh climates.

Mosul’s Traditional Houses

In Mosul’s Old City, homes are built around central courtyards or hoash, creating privacy and temperature regulation. Features like iwans (vaulted halls), riwaqs (colonnaded galleries), and shanashil (wooden projecting balconies) define the architectural vocabulary. The sirdab – a basement level used for cooling during hot summers – is common in both elite and modest homes.

The Beit al-Tutunji mansion, built in the 1800s for an Ottoman official, showcases these elements in their finest form: intricately carved arabesques, Arabic calligraphy, geometric motifs, and a large marble courtyard surrounded by rooms with high ceilings and stained glass.

Najaf’s Courtyard Dwellings

In Najaf, houses reflect similar values but with a stronger emphasis on modesty and religious privacy. Homes often feature bent entrances to block direct views from the street, and upper-floor ursi rooms – cool sitting areas with wooden screens – extend over narrow alleys. Like Mosul, Najafi houses include sirdab basements and wind towers that regulate airflow.

Basra and the Shanasheel Tradition

In Basra, the architecture is distinguished by ornate shanasheel, or elaborately carved wooden balconies extending over the street. These were common in the 19th and early 20th centuries and allowed women to observe street life without being seen, a functional and cultural innovation.

The Imam Ali Mosque in Basra, among the oldest mosques in Islam, originally used palm trunks and mud bricks. Although reconstructed multiple times, it remains a cornerstone of Iraq’s early religious architecture.

Restoration and Resilience

The destruction of Iraqi heritage during wars and extremist occupations has prompted international and national efforts at restoration. The Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Mosul, famed for its leaning al-Hadba minaret, was destroyed by ISIS in 2017 but is now being rebuilt using traditional materials and methods. Its planned reopening marks both a symbolic and architectural revival.

Similarly, Beit al-Tutunji was recently restored with help from UNESCO and revived as a cultural center, showcasing traditional craftsmanship like wood carving, plasterwork, and brick masonry. These efforts reflect an enduring desire to protect Iraq’s architectural identity from oblivion.

The Traditional Architecture of Iraq

Traditional Iraqi architecture is deeply rooted in its environment, religion, and cultural heritage. From the monumental ziggurats of ancient Sumer to the Abbasid mosques and courtyard houses of Ottoman-era cities, the architecture of Iraq tells a story of adaptation, identity, and endurance. Its reliance on passive cooling techniques, privacy-driven layouts, and skilled craftsmanship reveals a sophisticated architectural logic long before modern technologies arrived.

Today, as Iraq rebuilds from the traumas of war, its architectural heritage stands not just as a memory of the past, but as a foundation for renewal.

Ralph Hage is a Lebanese American architect who divides his time between Lebanon and the United States.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!